The Story so far...

1970's- FM radio, Alternative Magazine & 1st US Indie Distributor of Euro Rock

1980's- D.I.Y. LP + Cassette & CD label

1990's- Distribution via the WWW

2010- Eurock.com ~ Multimedia Podcasting, Interviews & Reviews.

Label & Artist Submissions Accepted for Review...

Klassik Krautrock

Artistes Français

|

Mikhail Chekalin INTERVIEW

The history of experimental music from the East European countries for the most part is based primarily on which music and musicians managed to escape their individual countries via clandestine channels. The sporadic release of such music in the West, and low level of publicity it garnered marginalized it for the most part. There were but a few exceptions. Interviews with musicians from those parts are still rare even today.

Now that the East/ West barriers have come down literally, the Internet has made everything and everyone more accessible, theoretically. The underlying irony being that the flood of information itself offers so much in some ways that it serves to obscure all but the most promotional and savvy in terms of the technology of exposure. Left out in both cases then and now were/ are often the most creative and ground breaking artists.

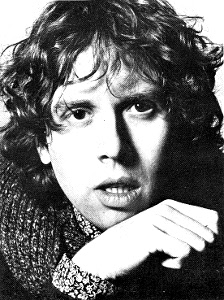

Mikhail Chekalin is one of those. Arguably he is the most influential modern composer of the last 35 years in the former USSR, now Russia. His work was experimental; in fact his creative intent was specifically to break new ground stylistically. He worked outside the boundaries of established culture, while at the same time breaching its borders when possible to make his point and music heard.

Over the span of his career Chekalin has produced some 30+ works that range the sonic spectrum for Post Pop, to free-jazz, electronic, and Post Symphonic. While his music was known to me since the 1980s, it was only recently that through word of mouth he contacted me via the Net. In the past year he has sent me most of his albums, and I have been amazed by the spirit and high level of creativity embodied in the sum of his work. From that contact followed a series of conversations, and at last this interview. What appears here is an abridged version of a very long manifesto of sorts that he wrote in response to my questions.

The resulting narrative history offers a fascinating overview of his passionate East European ideas and mindset grafted into the English language. Chekalins words and music which reflect a personal and philosophical grasp of the cultural dynamic I found to be absolutely fascinating in so many ways. The text was translated for him from Russian to English over there, and I made a few interpretive changes in places attempting to clarify what he was saying as I understood it.

The piece as a whole

makes for challenging reading, as well as a stunning personal analysis of the

dynamic contrast between the mainstream and Second Culture. In the end, I

think he is not only one of today's leading tuned in artists in the truest

sense of the term, but his story powerfully illustrates the universal truism -

if you do not learn from the past, you truly are doomed to repeat it. And no

matter the circumstances, art will find a way to persevere.

Archie Patterson

Q: Was it quite difficult to get exposure to Western pop culture and experimental music, and who the artists that were more known?

It is really sad,

that it seems hard to imagine that to get oneself exposed to the Western culture

in the USSR was not difficult at all. It was even less

difficult then it is nowadays. I will try to express my point more clearly. If we are talking

about the USSR at all we should draw some lines of distinction first. The USSR of the

1970s was one thing. The USSR of 60s was a USSR of the thaw. Art engaged should

stand for Official Art of the USSR as opposed to the Unofficial

Art I

suppose, though I am aware that is not quite the same thing.

Back then people

managed somehow to hear new music from the West. I can think of no far-away

Siberian corner (as it happens I had an opportunity to travel up and down the

USSR) not to speak of Moscow and its surroundings, where they were not listening

to some recent Deep Purple, Led Zeppelin or Beatles album. It is true, it

used to be some umpteenth tape-recorded version, so what. People used to come

from another city just to listen to these stereo-sound recordings. In the 70s

and 80s it was the same story with video.

The reigning atmosphere here was liberal indeed (with all due reserved for the Soviet Deputy Powers). Maybe in comparison with the Western countries it did not seem so, but there was nothing of the same order of things with us in Moscow. This liberality was exercised even more in the Soviet Baltic Republics: Estonia, Lithuania and Latvia. Lithuanian rock-groups were permitted then, or rather they had been granted permission to have their discs released on the Melodiya label much sooner than some perfectly insipid, feebly unoriginal Western beat-style song from Moscow managed to navigate the barriers of obstruction to be issued as well. And, if and when, eventually, it got released, after having been arranged and pawed at by the representatives of contemporary Soviet music trend (Soviet Composers Union being the embodiment), it usually was released in such an awful arrangement that no traces were left of initial attempts at beat or rock.

Q: There was a state owned record label named Melodiya. Was it possible for artists to get signed to contracts to record their music and get paid like in the West?

Well, yes, it was

not difficult at all... what do you call difficulties, it depends. It is a fact

that there was no publicity going for the most recently recorded Beatles

album, that kind of thing, all the way around... how to get informed was

problematic. Now there was that Catch-22 of ours: you could buy a recording by

a mignon bearing the caption Vocal & Instrumental Music Ensemble (this

rendering sounds lame, but it was not as a matter of fact quite the same as a

western rock-band). So, you buy this mignons LP and on the back cover you find:

Music & Lyrics by J. Lennon and P. McCartney, printed in non-pareille. It was

a bad interpretation of that music.

At record shops under the Melodiya trademark you could buy Schoenberg or Stravinsky and Bartok LPs. These could have been issued either by the Melodiya itself or by a Polish or a Hungarian label. The other Eastern European Republics exhibited at times a good deal of liberality as well as fine sensibility existed. In countries of Eastern Europe there existed a highly sophisticated modern culture, of which point the Polish jazz and Polish cinematography are just one of the proofs.

Q: Perhaps there was an underground scene or maybe you had to get a license to play in public like in some of the other East European countries?

The unique

phenomenon of unofficial Soviet art has absolutely nothing to do with this sad

thing much-acclaimed as a Soviet underground scene, if we speak of art as a

craft and a profession and if we call a spade a spade.

It is a matter of

prime importance to divest oneself of this phenomenon that any underground scene

existed, as say in New York City of 60s. Especially if we are to speak of

underground in relation to Eastern Europe, then, you know it is not a big deal.

If you are to compare this with the Western world, truly liberal at that time

before it became as it is today, a cross between an enforced police law and

enforced therapy. But in comparison with the Soviet Union the latter does not

exist here by comparison.

I identified myself quite early as one determined to choose a music career for myself, not just as a performer, but rather as a composer. In this sense, I steeped myself in the 20th Century at large. It made no difference for me whether it concerned philosophy, or art in general, or music in particular. Sure, I had different priorities at different periods of time, and this or that influence might be traceable in connection with this or that age. But if I loved to show off throwing in all the citations and reminiscences which I have managed to amass when playing beat on the piano at a kvartyrnick (a session at some private flat) where I performed either as a rock-musician, or as, how should I put it correctly (the phrase free jazz was not in common use then) free music improviser; whenever I went to classes of composition I left all this stuff outside the doors. It would be correct to say that I fell under the influence of Hindemith, or Ligeti and Bartok. To be sure I submitted myself to influences, how could it be otherwise. And what is more, I still do not know whether I collected them all; I reckon I have been affected by too few.

Q: I first heard your music when a friend in the Estonia sent me an LP called Post Pop/ Non Pop on the Melodiya label. Did you always release your music on Melodiya, or did you have other previous underground releases?

Recordings are

underground-made; releases could have been effectuated only at Melodiya. That

was a State-owned firm-monopoly, there did not exist any other. It is exactly the

reason why to have ones works released at Melodiya was official recognition.

By conquering this institutional stronghold of the Soviet Empire one conquered a

place for themselves among those of a recognized rank.

As a matter of

fact, that subterranean recording studio of mine was not some stationary affair,

it was a movable feast, quite literally it was the very first of its

kind in Russia as early as the end of the 1970s.

When you did that you were in for real prosecution from the Law for having committed an illegal act, having produced a sound-recording without sanction by the proper authorities. If a score of people copied someones music (unreleased in particular) with the aid of a domestic tape-recorder, that also qualified as illegal, either as an abuse of the State-owned recording facilities in order to gain a private profit, or for the spreading of unauthorized information. So it is either a civil case or a criminal offense.

As for my music, if we speak of an

effectual demand in absence of real engagement, it used to have an

audience of 70 to 90 thousands; such were the number of visitors who frequented

the famous annual Exhibition of The Twenty Moscow Painters during the 80s where

the music was used as soundscapes played during the exhibition of those famous

painters works..

Today modernity has been all but abolished. The well-known words of Solzschenitzyn to that affect that were, do not forget to wipe clear the face of your watch has drawn a bottom line under the process. A modern culture had been carried on in the USSR, and then all of a sudden it just ceased to be, sometime during the 70s. Today one has got to carry on incognito, as it were, to go into hiding, but not into any sort of real underground.

Q: When Glasnost came about did it help you and other more experimental musicians, and does it still exist today?

In those days the

real giants were right over ones shoulder, here was Shostakovich and over there

was Solzhenitsyn; everybody realized that things were changing, the change was

almost upon us; those monsters present had been left nothing to do but go along

with the tide. People such as me were just the first wave hitting the beaches.

It was I, us, who achieved Perestroika, not Gorbachov.

Today it has been

eliminated. This current situation is a sort of state like cultural decay, and

culture of crisis. It is really quite the reverse from before. Basically it is

the case of turn-coats all over again. That was due to these very same people

who one would expect to be held responsible at last for all those shameful

indignities of the past, petty compromisers who were so eager to please,

catering to the ideological demand in the 1970s in some manner for their

employment by this corrupted intelligentsia. Formerly they acted as loyal

attendants for the former Soviet authorities; they are again right there in the

old place, now in coalition with those who lack any form of intelligence. This

current situation appears to be one of total corruption.

Now fully

employed and in a position to draw benefits are those representatives of the

elder generation of cultural workers who were officially engaged during the

Soviet period. Together with those of much a younger generation who happen to be

their children, quite literally. Not in the figurative sense of the word however

in which we all in the past have been successors to our fathers deeds and

glory. Those singular

persons, those recognized names of repute in the modern unofficial culture of

the USSR of 70s and 80s, whose artistic masterfulness and expertise one would

expect was going to come in handy during the 90s, have been completely hushed

up.

Meanwhile we

observe a flourishing of such a thing as a culture of functionaries backed up

by a newly established mass media of glamour magazines which manipulate the

cultural news to the benefit of those officials functioning in the sector of

culture, without regard for their competence or the lack of it, and to the

exclusion of everything else. Not going into the particulars, I do not even

mention the yawning absence of a national sound-recording company comparable to Melodiya in the scale of its national and world-wide activities.

As for attitudes

towards artists, it is not different to any significant extent. I would rather say

it is a counterpart of the former attitude notwithstanding its newer settings. In

the words of one of the great Russian cultural workers (to use again that Soviet

cliche) Pavel Florensky: what makes people leave Russia, why having

suffered from bitter mortification.

I would not say that it is a subject peculiar to Russia; it is rather a Soviet peculiarity, and as I was born in Soviet times it strikes a deep note with me, a note of piercing anxiety, I just hate like hell to pedal it.

Q: Now that the USSR and CP are gone has the cultural climate improved to offer more freedom for artists in Russia?

That is the point;

that is what the drama of solitude is all about. In fact, there is an

anti-Glasnost of such monstrous dimensions now as we never knew during

the time of Brezhnev. Back then freedom was present by implication, it existed within

the rule since no one such particular thing did not exist, and then nothing

else exists either. Things were so self-evident then that it revealed an

infinity of possibilities; one held ones head high and having virtually no

means invented means by which to win people to ones cause, to make them need

and cherish something meaningful. Anything, everything was possible; a magical

metaphysics just worked itself; or one worked their magic.

Now it just makes

no sense; I realized. It is impossible to give an account of how one has been

composing synthesizer music when they owned no synthesizer. I remember I was

distraught when the US magazine Keyboard interviewed me in 1988, the occasion being having my

LP released at Melodiya. I was totally at a loss, how should I answer the

customary questions what synthesizers I have got, which I prefer. But I was not

amazed in the least, that at my age of the twenty seven I'd won a position

within this stronghold of Melodiya. I had found a way to establish a whole new

rubrique, have a new genre approved. Even as I took account of my circumstances,

I was sure on my own account that I did not just beat about around the bush,

wasting my time. That is, come what may, having my guiding light, I was bound to

come up with a result, no null and void, horror vacuum for me, in a manner of

speaking.

Since I was sixteen years old I knew what it meant to impersonate an artist, especially in such a country as USSR, what part an artist has to play. Even then, every dirty rocker in USSR knew his part by heart, without ever bothering to put it into words. It is a pity that almost the whole lot of them lost their chance to mature, did not reach beyond that boyish-infantile social rock of theirs, and got trapped in simply second-hand music-making.

Q: When you began making music what was your emphasis, a sort of pop music, electronics, or?

Quite early on I

was determined to make a music career for myself not just as a performer, but

rather as a composer. An oratorio, a composition for a mixed chorus and an

orchestra, which I wrote in 1975, was a landmark for me indeed. So I date my

professional existence from that event.

It was at a later date that I did something more on a synthesizer. At the beginning of the 1990s there appeared press reviews, some dozen and a half of them, concerning my album Night Pulsation on the German Erdenklang label. That was a sort of breakthrough perhaps as the first disk of a Russian composer to be released on the international electronic scene. The reviewers are quite correct in pointing certain influences they chose to remark upon. If they wish to see those works of mine as being influenced by the heritage of Stravinsky and Rachmaninov, so let them. In fact, I am really grateful for their comments.

Q: What kind of music are you currently working on? And will you have a new album coming out in the near future?

Well, now, I

work-around-the clock, non-stop since I am a composer, so all kinds of things may

come to pass. Is there a demand for it? For sure, I am certain there is; the very

thing that I create is in demand. Whether it is sought after from a commercial

point of view, is still another matter. In order for my kind of work to actually

get widespread recognition however perhaps a revolution would have to occur. And

some form of revolution is pending in the world no doubt of it; that there is a

change in the air is indisputable. That is why an artist is a great futurist by

nature. In earlier days, when I delved into the past I was really reaching for

the future. So then, I am of the opinion that over the span of all three decades

of my career I have been engaged in a very serious piece of work, and I am not

going to ever change that.

I have made my

presence more known due to my electronic works. The music for one of them

Last

Seasons was executed in a most conventional way. Done as if I composed a

traditional score, drawn from a vocabulary based on a mode of expression from a

19th century heritage. It was an act of rebellion on my part I

would say.

It would be excessive, to enlarge on the meaning of this work. I do however

consider it to be of importance as there is no other opus for all I know which

played up this canon of a genre. There is still another work of that sort on CD,

under the title Black Square.

Another, among my

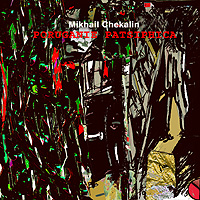

more recent ones, is Porughaniye Patsifika (The Desecration of a Pacific

Sign). I doubt anyone in my country is going to come up with an offer to

release it as an audio CD. I have already mentioned the abolishing of any national

institutional recording label in Russia. Since Melodiya has been torn down

there is no other label comparable to Deutsche Gramophone, for example, or

even to BIS or Chandos which are meant to release new styles in classical or

jazz. Here nothing exists that is even remotely recognizable as a national

policy in sound-recording in terms of promoting our national culture. The late

Melodiya recording operation is literally conspicuous by its absence. There is

no market for music officially.

Today there is a

pseudo culture of imitation playing a vile trick on the genuine

rock-music-culture here which has now been forced out and doomed to a state of

everlasting amateurism. This cultural wasteland has supplanted our music-scene

which was stripped in the process of all value it might have possessed becoming

now second-rate. There was nothing progressive about it and never could be.

Things were very similar within electronic music in terms of being considered as

art and part of a progressive-music-scene. That was non-existent in the USSR. In

fact there were composers who having full sanction from on high, and I do not

mean the High Heavens for sure, used to receive commissions to make electronic

music. Only what kind of electronic music was that, when they summoned an

orchestra to produce an orchestral-sound; then they summoned a rock-group to

produce a rock-group sound. In reality that was just music where they played a

synthesizer along with all the other instruments.

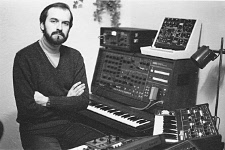

That is why I was not keen on electronic music, but, as fate would have it I have been set face to face with such a problem that if I were to achieve my ambition as a composer, to be able to realize my conceptions I should learn to perform this way myself. I racked my brains to find a way around that; but in the end became reconciled to use the method of electronic music compositions to achieve my desired creative and compositional goals.

Mikhail Chekalin: PORUGANIE PATSIFIKA (A Post-Symphony in 9 Parts) (CD)

Released

now on CD by Mir Records PORUGANIE PATSIFIKA represents the first musical production in the USA

by Mikhail Chekalin. The music was recorded in 2005

for a film shot during 2006 based on the paintings of a group of

well-known Moscow artists known as founders of the Soviet unofficial art

movement of the late 1960s-1980s, the famous Twenty (20 Moscow Artists at

Malaya Gruzinskaya Street). Their original works are now stored in private

museums and collections.

As the title implies the music is Post Symphonic in the sense that it echoes the symphonic form of the past perhaps, but goes beyond that genre stylistically by infusing into that spirit a neo-electronic palate that bears little resemblance to the experimental style of the German influenced Euro scene, or pop music.

Upon listening it

is obvious that Chekalin has an innate understanding of multiple styles and

genres. He has not so much learned them as lived and thoroughly absorbed them

into his consciousness. So the resulting music is totally organic, not simply a

fusion of styles in any way. He combines melody, compositional dynamics, and

sonic tone colors in myriad layers and striking ways. Each composition

creatively embodies the spirit of the art used in the films imagery. The

combined affect creating a unique conceptual audio/visual experience as you listen.

After a few

listens I think one could say that The Desecration of a Pacific Sign

represents not only the best of the past, but a step forward creatively for the

future of electronics musically. It channels the spirit and energy of a former time, and by

some alchemical musical process brings it alive, unprocessed and unadulterated,

creatively exploring new sounds and compositional styles in this brave new world

of the new digital domain.

Chekalin also has 2 other productions Paradigm Transition & Untimely completed which comprise the other parts of his most recent post symphonic musical triptych. These titles are set to come out on Mir Records before the end of 2007.

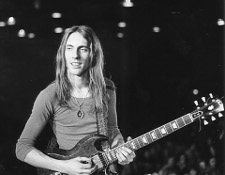

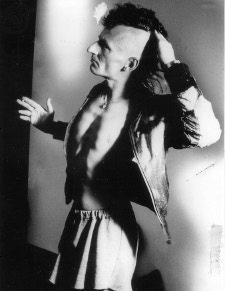

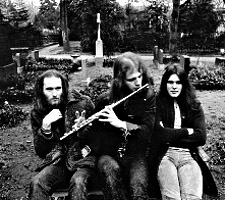

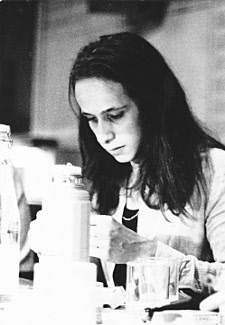

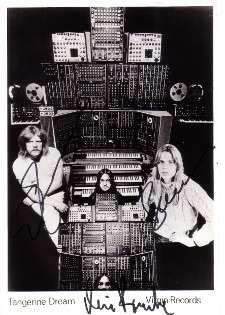

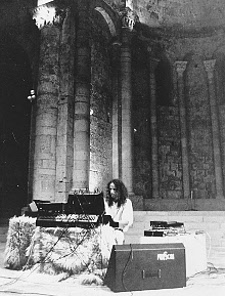

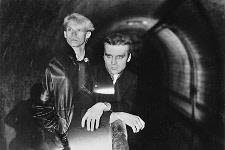

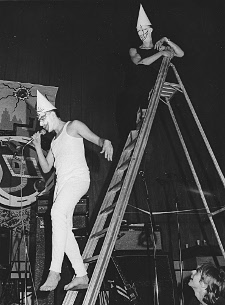

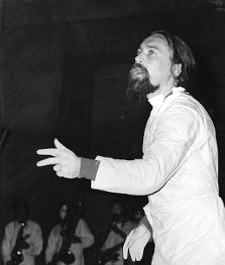

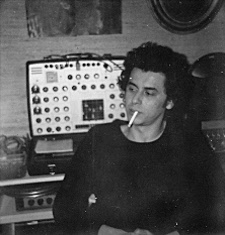

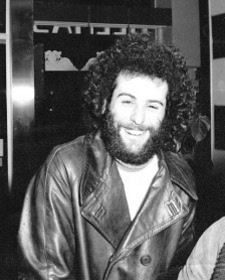

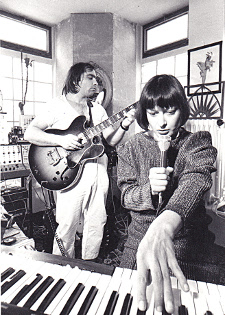

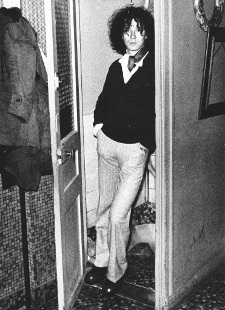

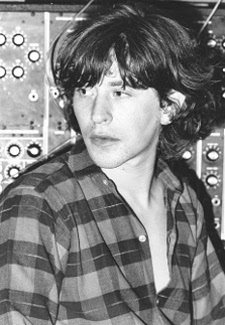

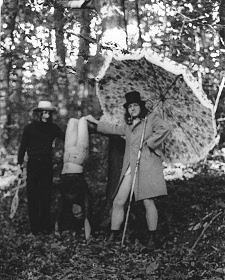

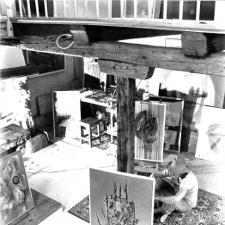

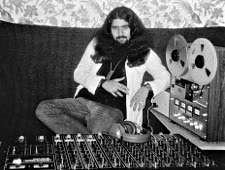

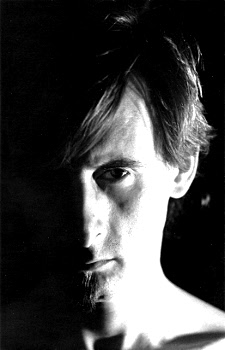

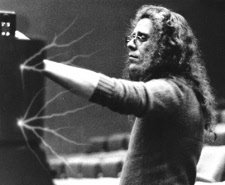

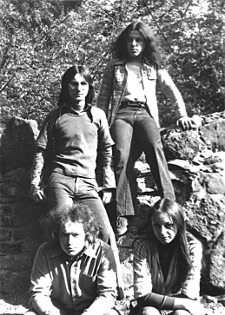

[Accompanying images are slides created by Mikhail Chekalin from live performances by in his Electronic Music & Light Graphic Dynamics Experimental Studio in the 1980s.]

reviews features podcasts email bio

reviews features podcasts email bio