The Story so far...

1970's- FM radio, Alternative Magazine & 1st US Indie Distributor of Euro Rock

1980's- D.I.Y. LP + Cassette & CD label

1990's- Distribution via the WWW

2010- Eurock.com ~ Multimedia Podcasting, Interviews & Reviews.

Label & Artist Submissions Accepted for Review...

Klassik Krautrock

Artistes Français

|

'When

modes of music change,

the fundamental laws of the state always change with

them.' Plato

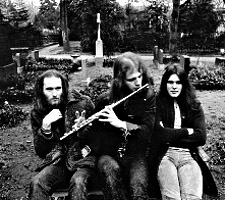

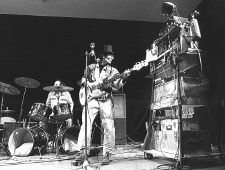

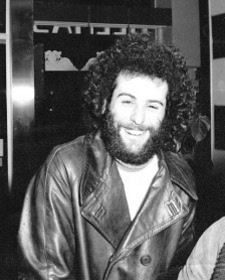

The Plastic People of the Universe

The Plastic People of the Universe are a band who made music as an act of creation for a less material second culture, not centered on marketing and selling. In the process, the Czech government banned them and various members were thrown in jail. The government informed them they had to obtain a license to perform or quit playing. They then went underground and played secretly. Their earliest music recorded underground were tapes for their first two albums, Egon Bondys Happy Hearts Club Banned and the Hundred Points. Smuggled out of the country both were released by indie labels in France and the USA respectively.

For 20 years the band continued being jailed and performing until the mid 1980s when pressure for around the world, especially the international human rights organization Charter 77 led by Vaclav Havel, got them freed. Ultimately, in 1989, the Velvet Revolution occurred in Czechoslovakia and the communist government was overthrown.

The Plastic People broke up in 1988, but reformed in 1997 when then President of the Czech Republic Havel invited them to perform for the 20th anniversary of Charter 77. The surviving members of the band are still performing today.

What follows here is a historical recounting of that period featuring original documents. In this laissez fair day and age, it may seem fantastical that they were persecuted simply for playing rock music. It is true nonetheless and perhaps that is why music today has become more of a commodity than the soul and spirit of youth back as it was back then.

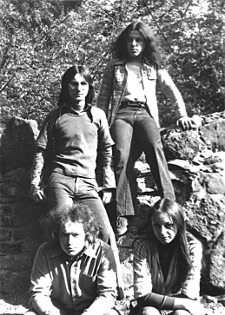

The group came together in the wake of the Prague Spring, 1968, a month after the subsequent Russian Invasion, tanks rolled down the streets of Prague toppling the liberal communist government of Alexander Dubcek.

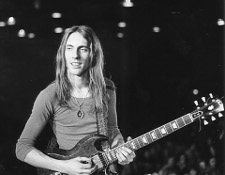

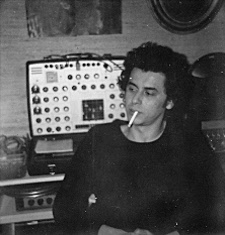

Led by bassist Milan (Mejla) Hlavsa, who had been in various bands previously, the Blue Monsters, Vagabonds, Primitives, a/o, the PPU took their name from The Mothers of Invention song of the same title on Absolutely Free. Their other musical influences were loosely the Fugs, Captain Beefheart and the Velvet Underground. Later in 1973, Hlavsa also was involved in another infamous Czech underground band DG 307.

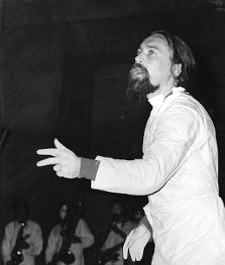

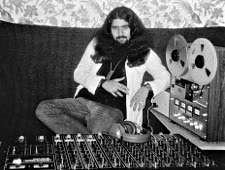

In 1969, Czech art historian and cultural critic Ivan (Magor) Jirous became their manager and artistic director. The following year, Canadian Paul Wilson, who had been teaching English in Prague, became the bands English tutor so they could sing in English the lyrics of the American songs they covered. He also translated their original Czech lyrics into English. Along with keyboardist Josef Janicek, viola player Jiri Kabes and with Paul Wilson as lead singer, the band performed professionally.

In 1970, their performance license was revoked when they refused to audition before the Ministry of Culture. In effect, they were banned, and their equipment confiscated. Subsequently, they went underground playing at weddings, parties and spontaneous happenings in country barns and basements in town. From that time on, they operated always in fear of arrest by the authorities and were in and out of jail on several occasions.

Ivan Jirous on 'Second Culture' in his Report on the Third Czech Music Revival:

I always felt angry towards other relatively decent rock groups when, in the early seventies, they began to try to make an official name for themselves, when they surrendered to the establishment demands for the right to play any kind of music whatsoever. Why did these musicians do it? I think it was because they lacked, and still lack, an understanding of what art is, what its function in the world is, and what the responsibilities of those who have been given the gift of creativity. The Plastic People maintained their integrity not because they were good musicians: in other rock groups of the time, there were better musicians. But in the most difficult period, when the plastic lacked equipment, when they had nothing to fall back on and no public prospects, one thing was clear to them: it is better not to play at all than to play music that does not come from ones convictions. It is better not to play at all than to play what the establishment demands. Even that is putting it too mildly. It is not better, it is essential.

The establishment has no power to prevent playing those who reject all the advantages that flow from being professional musicians. The establishment can only put pressure on those who what to be better off than the rest. For those who want to lead a better life, not in terms of material security, but in the sense of following the truth, the long arm of the establishment is too short. Only artists who understand that they have been given the gift of art so that through it they may celebrate those close to them will be worthy of being called artists. The great artist of tomorrow will go underground, wrote Marcel Duchamp, at the end of his life. He did not use the word underground to indicate a new trend. He meant the underground as a new mental attitude of the honest artist reacting against the dehumanization and prostitution of values in a consumer society.

In the West, many people who because of their mentality could be counted among our friends live in confusion. Here the lines of demarcation have been drawn clearly once and for all. Nothing that we can do will possibly please the representatives of official culture because it cannot be used to create the impression that everything is in order. Things are not in order.

There has never been a period in human history that could be considered an exclusively happy one, and genuine artists have always been those who have drawn attention to the fact that things are not in order. This is why one of the highest aims of art has always been the creation of unrest. The aim of the underground here in Bohemia is the creation of a second culture, one that will not be dependent on the official channels of communication, social recognition, and the hierarchy of values lain down by the establishment. A culture that helps those who embrace it rid themselves of the skepticism, which says nothing can be done when those who make the culture desire little for themselves and much for others.

The band continued undaunted nonetheless recording during that time their first album underground entitled, Egon Bondys Happy Hearts Club Banned. The lyrics for that album were writings by the famous surrealist dissident Czech poet Egon Bondy. He was one of the most prolific Czech writers and philosophers publishing over 50 books of poetry, history and philosophy during his life most of which were only published and distributed in the literary underground. The primitive music of the PPU coupled with his minimalist lyrics make for some of the most raw and compelling music, you will hear.

The tapes for the album were smuggled out of Czechoslovakia to France where Jacques Pasqier created a new label, SCOPA Invisible, and released it in 1974. He made contact with me early in 1975 asking me to handle promotion and distribution via Eurock in the USA. The release of that album and the subsequent press generated a minor sensation worldwide. As it later turned out, the release of that album played a part in the movement that led to the formation of the Charter 77 rights organization. During this time, the band was constantly harassed and Jirous was jailed. In spite of that, they continued sporadic performances.

At the bottom of a letter I received in 1980 was the notation, 'Remember to use pseudonym'.

It included several articles relating to the Czech underground from Toronto updating me on the Plastics situation in Czechoslovakia. .

I do not like talking about the PPU in relation to politics because their music has more to do with human relations. But I can not avoid it because the first thing I am always asked is, are they out jail yet?, as if jail were some kind of bottom line from which to judge the tolerability or intolerability of their situation. The short answer to the question is no, but a lot of other people in Czechoslovakia are, including some of the bands more active fans who were imprisoned for spreading tapes of underground music around and letting banned singers perform in their flats, along with other heinous crimes against the state. Ivan Jirous, the artistic director of the Plastics, was released from his third prison term last April, and as far as I know, has not yet been rearrested. Apart for that, there are still dozens, if not hundreds of people in prison there for their contribution to the cause of human rights, and the situation shows every sign of getting worse. Therefore, the fact that the PPU are not now in prison is good news only in relation to the vast sea of bad news that surrounds it.

The second question I am frequently asked is, are they still playing? The answer here is yes, but again, it should not be interpreted to mean they are gigging around the country, skipping from secret venue to secret venue like scarlet pimpernels, on-step ahead of the secret police. The fact is that since 1972 they have never played a normal, fully public, aboveground concert. Since the bands arrest in 1976, they have been constantly harassed by the police and as a result have only managed to perform before a live audience two or three times. Each time, however, they have performed a major new work, an amazing feat considering they have practically no place to practice. I have tapes of these pieces, and I believe that their new music will assure them of a place in some eventual revisionist history of rock (if it ever gets written, quite apart from the unusual circumstances that shaped that band and made them, for a time at least, a success de scandal in Europe or North America.

The first piece is called the Hundred Points It was recorded live at the Third Music Festival of the Second Culture on October 1, 1977, and the piece has an interesting history behind it. When the band was first arrested in March 1976, an article appeared in an English left-wing paper quoting some of the Plastics lyrics, including a long, heavily political song called the Hundred Points that the Plastics had never done, let along seen. I was in Prague at the time when I saw the article and when I saw the article. I was livid because the communist press had been printing vulgar lyrics the Plastics had never sung to discredit them (see Eurock Vol.2, No. 2 for example). Now the left wing press had descended to the same kind of falsehood, though with the best intentions, (the ends justify the means) in order to make the Plastics palatable and sympathetic to people who could only hear what the music was saying if the ideology was right.

When I showed the article to the band, their reaction astonished me. They said, There is only one thing we can do now, do it!

It was a brilliant solution. Rather than going through the rather complicated hassle of denying the Hundred Points, they simply had it translated into Czech and set it to music. Thus, they made the article in the English paper retroactively true.

The recorded Hundred Points represents a breakthrough for the PPU. First, it was their longest and most complex piece of music to date, and to deal with it they expanded the band to include strings and other sound effects that gave their music a new dimension in sound as well as scope. Secondly, it represented their first excursion into handling lyrics that were overtly political. How brilliantly they dealt with the whole situation. The music is completely free of any anger, sarcasm or exaggerated sentimentality that usually goes along with politically engaged art. Through the music and delivery they transform what could have been simply a cheap, declamatory text into a liberating affirmation of their own strength, the strength of people who have utterly rejected what the establishment has to offer and gone on to create something far better in its place.

A Hundred Points

They are afraid of the old for their

memory.

They are afraid of the young for their innocence.

They are afraid even of schoolchildren.

They are afraid of the dead and their funerals.

They are afraid of graves and the flowers people put on them.

They are afraid of churches, priests and nuns.

They are afraid of workers.

They are afraid of party members.

They are afraid of those who are not in the party.

They are afraid of science.

They are afraid of art.

They are afraid of books and poems.

They are afraid of theatres and films.

They are afraid of records and tapes.

They are afraid of writers and poets.

They are afraid of journalists.

They are afraid of actors.

They are afraid of painters and sculptors.

They are afraid of musicians and singers.

They are afraid of radio stations.

They are afraid of TV satellites.

They are afraid of free flow of information.

They are afraid of foreign literature and papers.

They are afraid of technological progress.

They are afraid of printing presses, duplicators and Xeroxes.

They are afraid of typewriters.

They are afraid of photo telegraphs and telexes.

They are afraid of automatic telecommunications with abroad.

They are afraid of letters.

They are afraid of telephones.

They are afraid to let people out.

They are afraid to let people in.

They are afraid of the left.

They are afraid of the right.

They are afraid of departure of the Soviet troops.

They are afraid of changes of the ruling clique in Moscow.

They are afraid of d�tente.

They are afraid of disarmament.

They are afraid of treaties have signed.

They are afraid for the treaties have signed.

They are afraid of their own police.

They are afraid of the spies.

They are afraid for their spies.

They are afraid of chess-players.

They are afraid of tennis-players.

They are afraid of hockey-players.

They are afraid of gymnast girls.

They are afraid of St. Venceslas.

They are afraid of Master Jan Hus.

They are afraid of all the saints.

They are afraid of gifts to the kids on St Nicholas.

They are afraid of Santa Claus.

They are afraid of knapsacks being put on the statues of Lenin.

They are afraid of archives.

They are afraid of historians.

They are afraid of economists.

They are afraid of sociologists.

They are afraid of philosophers.

They are afraid of physicists.

They are afraid of physicians.

They are afraid of political prisoners.

They are afraid of the families of prisoners.

They are afraid of todays evening.

They are afraid of tomorrows morning.

They are afraid of each and every day.

They are afraid of the future.

They are afraid of old age.

They are afraid of heart attacks and cirrhosis.

They are afraid even of that tiny trace of conscience that may still be left in

them.

They are afraid out in the streets.

They are afraid inside their castle ghettoes.

They are afraid of their families.

They are afraid of their relatives.

They are afraid of their former friends and comrades.

They are afraid of their present friends and comrades.

They are afraid of each other.

They are afraid of what they have said.

They are afraid for their position.

They are afraid of their position.

They are afraid of water and fire.

They are afraid of wet and dry.

They are afraid of snow.

They are afraid of wind.

They are afraid of frost and heat.

They are afraid of noise and peace.

They are afraid of light and darkness.

They are afraid of joy and sadness.

They are afraid of jokes.

They are afraid of the upright.

They are afraid of the honest.

They are afraid of the educated.

They are afraid of the talented.

They are afraid of Marx.

They are afraid of Lenin.

They are afraid of all our dead presidents.

They are afraid of truth.

They are afraid of freedom.

They are afraid of democracy.

They are afraid of Human Rights Charter.

They are afraid of socialism.

So why the hell are WE afraid of THEM?

Along with the documents came a master tape with artwork and 30 minutes of music the PPU had recorded, it was the Hundred Points. Eurock released it in 1980 as a cassette only production. That release generated a further heightened awareness and good deal of media about the Plastics music and human rights cause. The communication continued elaborating further:

In retrospect, the bands next step seems entirely logical: from political music that rise above conventional politics they moved on to music that transcend religion. In April 1978, they Plastics performed and taped what I think is their greatest work so far, their ceremonial Easter rock Passion Play. If the Who legitimized the rock opera, the PPU should be given credit for doing the same thing for the Passion play, an art form that has deeper roots in European musical history and theatrical tradition than opera does. People who take anti-religious sentiments for granted may find Passion Play somewhat difficult to penetrate until they realize that what the Plastics have done is to make an important human statement which is also, incidentally, a statement of their own faith. They have reinjected into a central myth of our civilization, the suffering and death of Christ, a sense of drama, immediacy, relevance and intensity that you will hardly find anywhere in Western music of this genre this side of Handel. The focus however is not so much on the divinity of Christ or the revelation of divine order in the universe. It is on the fate of a man who comes forward with a message of truth, which is in fact a radical vision that raises the humble, the poor, the sick and the outcast to the status of inheritors of the earth.

Of course, he is betrayed, tried and put to death by his own people because law and order in this outpost of the Roman Empire is more than justice or truth. As the PPU present it, belief in the story of Christ is not a matter of suspending your rationality, but simply of having your eyes open. The passion of Christ becomes a direct representation of life in a dictatorship, where friends can become police informers and people are jailed or hounded to death or driven into exile for simply trying to live by the truth as they see it.

Even if you knew nothing about that however, were agnostic or atheistic, and did not understand Czech, the music itself is magnificent and compelling. It is by far the best synthesis of theme and sound that the bad has ever achieved, proving again, as all great works in the rock tradition have done, that rock is still a medium of infinite flexibility and infinite capacity to absorb other forms and influences while remaining inspired and inspiring at the gut level.

The Plastics, according to a rumor that just reached me have apparently completed another major piece of music, which they recorded this past summer. Entitled, Jak ude po Smrti (How to be Dead), as far as I know no copies have reached the West. They have been working on it for well over a year: putting the works of Czech philosopher Ladislav Klima (1878-1928) to music. Klima is one of the most uncompromising philosopher who ever lived, constructing his philosophical system on the premise that reality is entirely intellectual, that is, a product of mind. He wrote strange, metaphysical horror stories and gory, gothic pornography. The regime banned his work, but he is popular among young people in Czechoslovakia for his total rejection of materialism, which, you will recall, is the official basis of the ruling ideology. All I know about the music is that Milan Hlavsa, who wrote it, says it is horrible, which does not surprise me because in the radical esthetic of the Czech, underground beauty is anything but reassuring, and Klima himself believed that in their most intense states, beauty and horror were the same.

Like all good music, that of the PPU and others in the Czech underground is meant to disturb, upset and question at the same time as it affirms. Once you have chosen to live in terms of your own truth, there is nothing left to do but march to your own drummer and dance to your own piper.

The International attention and heightened repression of the PPU by the government at that time became a major catalyst for independence from the communist party, which was spearheaded by the Charter 77 human rights organization.

The march of history however is sometimes a long one. It was not until two years after the recording that pressure began to build significantly internationally. There was a Press Release, and Petition, which began to be circulated.

Press

Release

September 20, 1982

On Monday, September 27, the appeal trial will be held of Ivan Jirous, art historian, rock critic and manager of Czechoslovakia� foremost underground rock group, The Plastic People of the Universe.

Jirous is appealing a 3 and a half year sentence in a maximum-security prison on charges of disturbing the peace and drug possession. Appealing with him are three other activists in the cultural underground, Frantisek Starek, Michal Hybek and Milan Eric.

A report by VONS (the Czechoslovak Committee to Defend the Unjustly Prosecuted) makes it clear that the charges against the four men are groundless. They are also in contravention to the Helsinki Agreements and the UN Covenants on Human Rights, the four are really being prosecuted for their activities in the unofficial rock culture of Czechoslovakia, of which Jirous is the spiritual father.

Amnesty International has officially adopted Ivan Jirous and three others as prisoners of conscience and is campaigning on their behalf.

Friends of Ivan Jirous, led by Vratislav Brabenec, the former sax player of the Plastics now is now living in exile in Vienna, are planning a series of actions in his defense, in cooperation with Amnesty International.

On the 22, 23 and 24th of September, a series of demonstrations will be held in front of the Czechoslovak embassies in at least 10 different cities in the West.

In Canada, the events are being coordinated by Paul Wilson, who spent ten years in Czechoslovakia and played with the Plastic people. A series of benefit concerts are also being planned.

A petition demanding the release of Ivan Jirous and his friends is being circulated around the world. Musicians, artists, writers and other concerned individuals are being asked to sign.

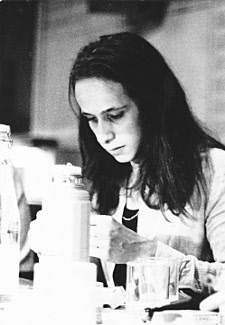

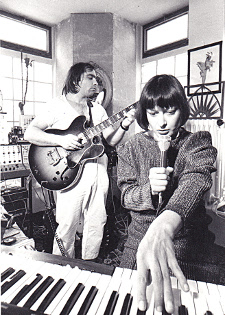

Ivan Jirous ultimately was released. The PPU broke up in 1988 with several members, Hlavsa, violist Jiri Kabes, and keyboardist Josef Janicek forming a new band called Pulnoc (Midnight), featuring female lead-singer, Michaela Nemcova regarded as the Czech Nico. They recorded and released an album in the USA on Arista. Hlavsa later worked as well with a new band Fiction. He passed away in January 2001.

In 2006, Ivan Jirous was awarded the Jaroslav Seifert Prize in Czechoslovakia for literary achievement based on his poetry and the more recently published 500-page collection of his letters from prison.

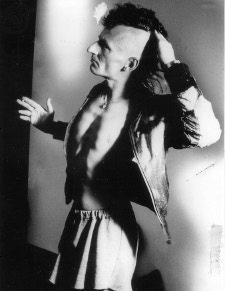

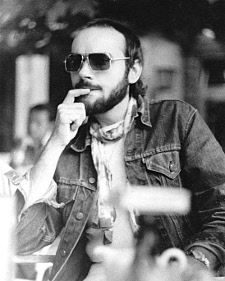

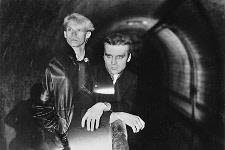

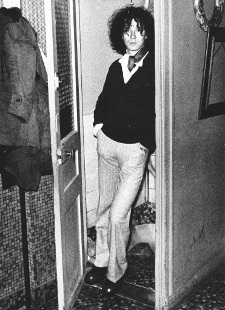

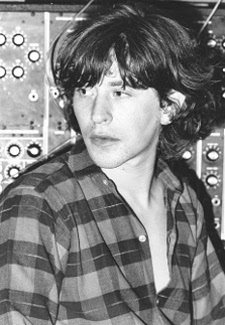

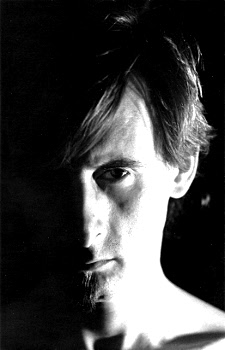

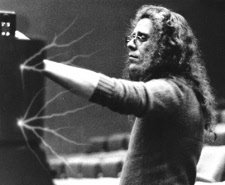

[Ivan Jirous & Paul Wilson 2006]

One of the most prominent Czech dissidents of those times, and a major supporter of the Plastics as well as Charter 77 was Vaclav Havel. His involvement with that human rights manifesto brought him international fame as the leader of the opposition in Czechoslovakia; it also led to his imprisonment. Havel was a major supporter of the Plastics and virtually by himself secured their legacy as the symbol of Czech artistic dissidents who led the fight for cultural freedom in their country.

Ultimately, in 1989 the Velvet Revolution occurred in Czechoslovakia. Vaclav Havel became the tenth and last President of Czechoslovakia (1989 to 92), and the first President of the Czech Republic (1993 to 2003). History was made in no small part due to the PPU and their principled refusal to submit to the authorities and standing up for their right to be free, to create art instead of commerce. The Plastics reformed in 1997 at President Havels invitation. He invited them to perform for the 20th anniversary of Charter 77. Today the remaining musicians from the band have remained active.

That brings us back to Plato and his declaration about music. On the face of it, what may not be apparent is that he issued it not as an invocation for freedom and change, but instead a warning about the power of music to subvert the establishment. He was attuned to a universal truth that has held true for generations.

Since the dawn of the 20th Century, a new era of technology, and Leo Fenders guitar, bass, and amplifier designs in the 1940s, the face of modern music has undergone a revolutionary process of change that continues now on into forever. Add to all that the reel-to-reel tape machine and a new musical mode was created from a fusion of black blues, country, folk, and jazz, a mutant cultural offspring. That deviant son - rock and roll - ignited a cultural revolution worldwide, which received more than its own fair share of cultural backlash from the mainstream culture.

In the beginning, it was labeled race music. A popular euphuism arose from that which made it very clear just what the new rock beat had liberated, dont come a-knockin, if the cars a-rockin. Ultimately, rocks primal urge led young people the world over to turn on, tune in their radio and record machines, crank up the volume, and experience the power of electric music for the mind and body, which literally rocked their world. The Plastic People of the Universe back in the late 1960s picked-up on this vibe loud and clear, staging their own cultural freak-out, which literally rocked and rolled the foundation of Czechoslovakia.

- Archie Patterson

reviews features podcasts email bio

reviews features podcasts email bio