The Story so far...

1970's- FM radio, Alternative Magazine & 1st US Indie Distributor of Euro Rock

1980's- D.I.Y. LP + Cassette & CD label

1990's- Distribution via the WWW

2010- Eurock.com ~ Multimedia Podcasting, Interviews & Reviews.

Label & Artist Submissions Accepted for Review...

Klassik Krautrock

Artistes Français

|

|

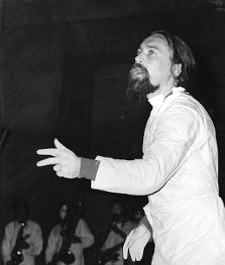

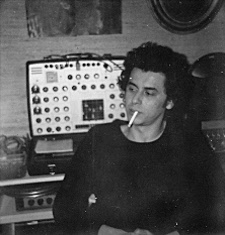

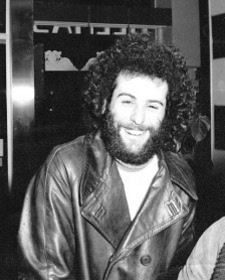

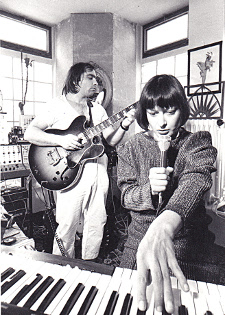

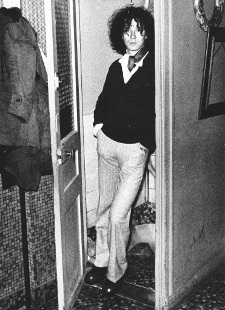

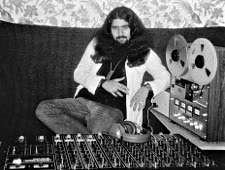

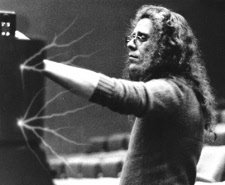

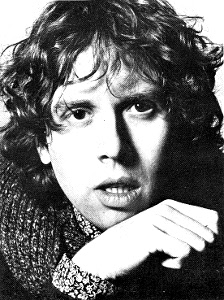

Giorgio Gomelsky INTERVIEW

“Une Histoire

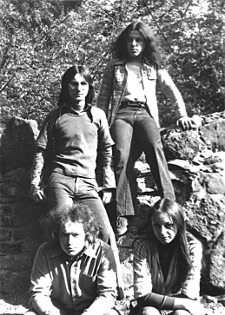

Personnelle de la Musique Underground en France If there ever was a man, who lived and breathed music it's the International vagabond Giorgio Gomelsky. Born in the former Soviet-Georgia, his parents fled Stalin and he grew up in France, Italy and Switzerland. As a teen he took, off and hitched all over Europe soaking up the influences of boho "existentialist" culture and tuning in to the jazz vibe that was influencing the scene. In 1955, he landed in London and with friends set up a little "Espresso Coffee Bar" where soon, many of the future Anglo scene makers hung out, getting a caffeine buzz late into the night. This embryonic idea turned into the prototype early London beat club (1956-1961) featuring fledgling musicians and bands playing rock' n' roll and skiffle. He wrote articles for music magazines, made a series of documentaries about the British jazz and the budding blues scene, and got involved in promoting the latter by opening a blues club later known as The Crawdaddy. During this period a young rocker by the name of Brian Jones hyped Giorgio on his new band, lo and behold called The Rollin' Stones, they got a residency at the club, which started them on their way to fame. The rock ‘n’ roll beat was growing louder and Giorgio was leading the way. Over a span of time the Stones, the Paramount’s (who became Procol Harum), the Muleskinners (who in part ended up as the Small Faces), Rod Stewart, Julie Driscoll, the Moody Blues, the Animals and the Yardbirds would all play there. During this time, as well Giorgio had made the acquaintance of another young buck that was kicking around ideas about making a film. As Bill Wyman recalls it, on April 14, 1963 he had a great surprise when Giorgio invited the Beatles to catch a Stones gig at The Crawdaddy and the two groups made their first contact. Ultimately the Stones signed with Andrew Loog Oldham and the Beatles with Brain Epstein going on to produce their Dadaist music film classic HARD DAYS NIGHT (hmmm, I wonder where that idea may have come from?). While secretly Giorgio must have been disappointed, to this day he carries nary a grudge, back then he barely skipped a beat. In 1964, Giorgio produced his first Rhythm & Blues festival featuring the Yardbirds, Spencer Davis Group, Long John Baldry, a/o. That led to his involvement with Mr. Relf, Clapton and the Yardbirds. Basically a blues band at that time, he recorded their very first album, and soon with Giorgio’s help, they were making records with sitars, harpsichords and Gregorian chants as well as touring the States. In 1967, he founded Paragon, a design, public relations and management company with a record label named Marmalade. London was swinging and Giorgio was making things happen, booking clubs, building a recording studio, recording and having great fun recording many soon to be "stars" including a young Vangelis In December of 1969, he had a falling out with Polydor Records and Deutsche Gramophone, companies who by and large had financed this adventure and he went off to France, his mother's home country. Upon arrival there, he reunited with old friend Daevid Allen who had been the Soft Machine’s guitarist and had started Gong in Paris. He began to get involved in the French music scene, met up with Magma and decided to manage them. His first move was to form a talent agency, Rock Not Degenerated - Rock Pas Degeneré. It ultimately became the number one employer on the European progressive rock scene. In 1970 with the recording and release of the first Magma album, le souterrain Français - the French Underground - began to generate rumblings. From that impetus a new spirit and correlating burst of artistic and musical energy was born. Along with that as well a new cultural and musical hybrid emerged that replaced the “chanson” with a uniquely fusion of the European classics - American jazz and rock, plus the distinct character of French culture. Within 3 or 4 years, Magma ended up playing some 60 concerts a year, to 2,000, 3,000 people and selling 150,000 albums in France alone. Today he lives in NYC since 1978. For the last 40 years, Giorgio has been the ultimate instigator and promoter of avant music. He has always been ahead of the curve stylistically and constantly striving to stretch the boundaries of rock music in general. More importantly, for fans of “Euro Rock”, he was at musical ground zero in France. The story he has to tell is fascinating, and Giorgio is a bard extraordinaire. So here we go… Q: What was the music scene like in France when you first went over there after working in the UK for many years? What year did you go there? January 1970. I had spent 15 years in London and had enough of the “perfidious Albions” as Napoleon called them! My mother was French, so I spoke the lingo, had family and friends there and visited the country often. While living in London (from March 1955 to December 1969) many French (and other “continentals” or “frogs” as the British called us!) were relying on me to interpret for them what was going on and then to arrange interviews with UK artists for TV, radio and magazines. I guess I was probably also the first of the “managers” in London to set up early club dates, tours and promotional activities in continental Europe. I did believe that if the “prophet goes to the mountain” it would pay dividends for the artists down the road. Besides, the local pop music scenes on the Continent were very “pasteurized” poor copies (and translations!) of US commercial stuff. Imagine a French version of “Tutti-Frutti”! I felt an injection of the energy developed in the UK by young and more “authentic” artists could help bring about a change in those countries music scenes too. Furthermore, I liked touring there; the food was so much better! Q: Who were the initial bands you heard? First of all, I had left England because after 15 years in London, I wanted some time to think about my life and my work, which was filmmaking. Although I managed to produce some documentaries in England, (all about music), I felt I now needed to concentrate on getting a feature film off the ground and get away from “managing” bands which I had taken up only because someone had to help the scene… ROCK & FOLK, a much-respected French music magazine, ran a long interview with yours truly and during the interview played me a tape of a French band, which somehow seemed puzzling to them and asked for my opinion. I remember it well, even today. The music was original, with influences derived from non-Anglo folk, classical, jazz and experimental music and, I said something like “very ambitious stuff, these guys seem to want to take on a lot, if they are really serious, it could be interesting.” There must have been a conspiracy, because wherever I went in Paris, people were asking me if I had heard THAT tape! It turned out to be MAGMA! I had rented a house in the country some 25 miles from Paris and started putting some order in my thoughts. I was living with a gorgeous French girl (Brigitte, later my wife), and my only ambition, after 15 years of intense work, was to do nothing at all for a while… A few days after the interview was published, I got a phone call from Faton, Magma’s pianist. They had read it and wished to ask me if I was interested in checking them out. I think they were playing one of their rare gigs a few days hence. No way, was my answer. No more taking on unknown (or any other) bands! I tried to explain to him I had gotten away from that scene and wished to sit under my tree and just watch nature and think. A few days later he called back. I got rather irritated and put him off as hard as I could. Brigitte however wanted to go to Paris to see her friends and, knowing me, suggested we should just go and have a good time, no strings attached. So, a few days later we went, and the rest is history. I had never heard anything like it. I was very impressed by their “sources” and their musical skills. This was not run-of-the-mill stuff. It also wasn’t “commercial” by any stretch of the imagination. But I’m a sucker for underdogs, so I was tempted to take on the challenge. At that time there wasn’t any scene whatsoever for “independent”, original music. The business in France consisted in descending order of the three great “auteurs-compositeurs”, Georges Brassens first among them, a true pipe-smoking poet, accompanying himself on acoustic guitar and setting to music his immensely perceptive insights into the French psyche and the infinite variety of everyday events befalling humans. Then there was Jacques Brel, a Belgian by origin, with a beautifully crafted repertoire of tightly woven, somewhat sad and yet comic anecdotes of love and descriptions of “marginal” characters. The third was Leo Ferre, a lion-like, ferocious and fearless social-critic-anarchist. All three were also great performers. After them you had people like Charles Aznavour, (known in the US for being in Truffaut’s films), Gilbert Becaud who wrote a number of songs which often got covered by US crooners and made him and his publishers handsome profits. Down the line there were other “variete” singers, mostly manipulated by the French music publishers’ fraternity, who hand in hand with the “major” record companies like Philips, Barclay. Vogue, etc., were really running the show. A French version of rock’n’roll consisting of cover-versions of US (and later British) hits had been provided for the younger generation, mostly represented by Elvis imitators like Johnny Halliday (who is still going!), Eddie Mitchell, Dick Rivers and other such “anglicized” rather contrived “acts”. They had originated in the late fifties from a small; more authentic rock scene based around the Golfe Drouot Club, but had soon been co-opted by the “business”, keen to exploit the young public. By the mid 60’s, based on the British model, a slew of rock bands were created by the “usual suspects” running the show. People like Les Variations, Les Chaussettes Noires, etc. With a few exceptions, none of them were any good really. Even if they could actually play, French just didn’t lend itself to rocking. The whole thing was a bit of a farce all over the Continent really. There were however some very good jazz musicians. Paris had been, still was to an extent, when I got there a center for jazz in Europe with a number of clubs, concerts, magazines and quite a few exiled Americans, like Kenny Clark and Bud Powell, and others. Here I must mention GONG. As you probably know back in London I had tried to help SOFT MACHINE get a recording deal, so I knew Daevid of course. I always felt bad for him because I was the one who in the summer of 1968 had sent them to St Tropez (a holiday resort in the South of France) to play in a club and get their stuff together. When they came back to the UK Daevid, an Australian citizen was refused entrance, so he had to return to Paris where he started GONG! Q: Was there any sort of organized scene? Other than the commercial one? No. Q: What was the cultural reference point of the French musicians? Were they as steeped in rock, jazz and other Western music styles as the British? As I said, after WW II Paris had been an important European jazz center. Unlike England where the Musicians Union did not allow foreign musicians to settle (!) Paris welcomed them and so many musicians from the States had settled there. First and foremost, Sidney Bechet in the late 40s, which opened up a New Orleans/Dixieland scene and later Bud Powell, Kenny Clark, Johnny Griffin and others who were “modern” jazzmen. They needed sidemen, so a local generation of jazz musicians sprung up. Mind you, Django Reinhardt’s Hot Club de France had achieved international success before the war, so there was a sort of a jazz tradition. Matter of fact Christian’s father Maurice Vander is a much-respected jazz pianist and accompanied many US jazz greats. Compared with England – or perhaps London - the big difference with regards to the development of “bands” was the lack of a local blues scene. However there was plenty of modern and avant-garde stuff. In 1968, BTW, while touring France with JULIE DRISCOLL and BRIAN AUGER, I had come across APHRODITE’S CHILD from Greece, stranded there by the May ‘68 events and I became friends with VANGELIS – with whom I worked later… Q: After getting there, how did you meet up with Christian Vander and the various avant musicians in Paris? Was there a specific club or area that they hung out in? Re: Christian see above. There were jazz clubs and two or three rock clubs, but as described above, there wasn’t a “progressive” scene as such. Q: Both the UK and USA had local areas that served as catalysts for a larger scene sometime later – was it the same in France? No! Q: When was the first time you saw Magma play live? How big was the audience? Around Easter 1970, there was an audience of around 300. They were about to release their first album. Q: At some point the scene started to grow and I’ve heard you and Magma + some others began to form a national circuit for concerts and promotion. How did the normal French music managers and club owners react to this? They just weren’t interested in that kind of music and with very few exceptions we couldn’t count on them. There were a few “Associations” (non-for-profit voluntary music lovers’ groups), but mostly they aimed to become “big time” rock promoters! I had to invent something else… Q: Who were the actual bands and people who instigated this circuit? Was it the bands themselves, their managers, agents, or? This is how it happened, literally! One afternoon I went to pick up Klaus Blasguiz, Magma’s lead singer, to take him to a rehearsal. He was teaching comic strip drawing in a youth center outside Paris. I was early, so I walked around the place and, behold, discovered there was a small theatre at the back of the center. I guess it could hold around 200 people. I freaked out, sought out the center’s director and asked him what kind of events they were holding there. “None.” he answered, “we can’t afford to book people…” Wow! I had a flash! It dawned on me there was a solution here, so I asked him if he would agree for MAGMA to play there, without guarantee or any money. We would promote the show ourselves, use his Xerox machine and the young kids to distribute fliers and give him 15% of the door and keep the rest. He thought that was a good deal and agreed to give us a date. This got my juices going, so I enquired how many of these “Youth Centers” (MJC – Maisons des Jeunes et de la Culture) there were and I found out there were some 200 around the country. Every political party seemed to have a “chain” of them, determined to recruit youth into their respective causes. Well, that was it! I got me a list of them and for a month I drove around Paris convincing them to go along with my plan. Just as in London with the blues in the early 60’s I was determined to get the music out there one way or another. I found 25 of these MJC – some (mostly socialist or communist!) more receptive than others, some with theaters and some with access to “community” spaces. To cut a long story short, a couple of weeks later, MAGMA did their first MJC tour. Five weeks, five concerts a week, a total of 25 shows. You better believe it a band gets pretty good after that kind of experience, besides we were actually making some money too, enough for the musicians to consider giving up their day jobs… From there I started to work on the rest of the country. Within a few months we had more than 120 venues, a complete circuit! Young people started getting interested in learning how to promote concerts, so we taught them how to form “associations”, get permits, etc., You might not believe this, but today, the major music promoters in France started with us. After our first tour I got GONG involved and then we formed an agency “Rock Pas Degeneré” and took in a whole bunch of groups, which had sprung up, like Crium Delirium and many others. Later, we invited British, German, Dutch bands like ART BEARS, CAN, SUPERSISTER, etc.; They in turn got the French bands gigs in their respective countries. Before long we had an international circuit…it was very cool! Q: I’ve heard some say in effect this underground activity was in fact a virtual revolution in terms of normal French music culture. Would you agree? Indeed…Before I left France in 1977, MAGMA were playing some 100 or so regular concerts a year in France alone and making between $5,000 and $10,000 a show. The last tour I went on was a double bill with LEO FERRE – who loved MAGMA – held in circus tents holding 5,000 people! Q: Can you explain how it actually worked – travel, logistics, booking, payments, etc? In the beginning we had to be very parsimonious, travel in old trucks/vans (I had a Mercedes and used to take five people with me) and stay with people, or in cheap (very cheap) hotels. France’s territory is not as vast as the US, so most distances were Between 100 and 200 or so miles. Payments had to be in cash of course, so we could eat, sleep and get to the next gig… Often, we just barely covered expenses. Later it got a lot better. But every time we played we were able to make friends and encourage the local scene. That really paid off! Q: Were the bands able to make good money doing this or was it more like, “art for art’s sake”? My view was that if the music was relevant we would succeed at building an audience, and, after a while, it would lead to our own little “market” and we could make a living at it, and so could many others. This happened. Q: At some point Magma got a large contract with the major label, Phillips. How did that come about? Did they receive a large signing bonus in advance as is usual in the music business today? I wasn’t involved in that, it was in 1969, before my time, but I know it wasn’t a “large contract”. Some of the musicians in that first edition of MAGMA were highly respected session men, like CLAUDE ENGEL, the guitarist. He knew people in recording studios and at labels. Q: What was the media and musical reaction like when they released their mammoth double LP in 1970? They had no idea. Some critics, the best ones, liked it very much. MAGMA always got good “press” such as it was at the time. I guess that’s the advantage of being active in a country where originality is respected… Q: Was that in fact the first French underground rock album to come out? I think so… Q: Did it open the door for more bands to make records? MAGMA was a trailblazer group for sure. With the addition of GONG the whole scene was spreading, so a lot of new energy came about. New magazines, like ACTUEL, helped a lot too and some radio and TV programs. People looked to MAGMA to fuel that energy, to be “taken aback”, so to speak. Q: Do you know how many copies of that first album were sold? No, but it’s still around. When I appeared on the scene I worked out an independent production deal with Philips and later with A&M and RCA (for my UTOPIA label). The LIVE at the OLYMPIA double album sold 150,000 copies in France, that’s like 300,000 “units”, as they say in the industry. Q: As an outsider I might guess that it in some way served to legitimize the scene. I say this because their second album received critical and cultural praise from more mainstream sources. So did the traditional French artistic tendency to encourage the avant-garde start to help the scene expand at that time? Well, good press didn’t actually get you gigs – there weren’t any in the mainstream - and anyway we had that under control. What really helped was the strategy of the “prophet going to the mountain”; so many people all over the country were encouraged, enfranchised to start local scenes. Now and then we got big engagements, like at the FETE DE L’HUMA every year, the biggest open-air event in France, and Christian got to write some film music, but above all we got credibility and people rallied around the cause, so to speak! This was during Pompidou’s reign, there was quite a lot of subtle repression going on, For instance, every time we had to take a toll road our van would be searched for hours and we always got to gigs late…but then we played for 5 hours, so that upset the “authorities”! Q: At its peak how successful was this idea of an underground circuit? Did the scene in France become highly profitable for record companies and artists alike? It completely transformed the scene by decentralizing it and by encouraging all sorts of local movements, like ALAN STIVELL in Brittany with his “Celtic” rock and the people in the southwest, with their “Occitan” poetry and music. Festivals sprung up everywhere. As I said above, record companies were just not interested in our stuff. We did everything a few independent labels and ourselves appeared and bands self-produced themselves. Towards the end of the ‘70’s, some of the original bands in the circuit disappeared, others, like CAN for instance, got very big indeed, relatively speaking. The “local” success allowed us to export our music to England, Germany. Etc., MAGMA did very well in England. We took that country by storm! Unfortunately, the 25-day tour that was to establish the band permanently got cancelled because of internal struggles and the subsequent breakup of the Vander – Jannik Top collaboration. That was when I left. Q: At some point however things began to change Internationally in the music scene and I’d imagine in France as well. Some say punk rock caused this change; in retrospect perhaps it was the inevitable and eternal creative cycle of events in the life of any social or cultural phenomenon. What happened to the underground scene in France? Punk rock was incorporated. The thing about Europe was, underground audiences were less divided and provided they liked what you were doing could support all manner of artists. The big event, in France at least, was that the socialists came to power and created a very strong Ministry Of Culture, which greatly encouraged native production. Had I stayed on I’m sure I could have gotten them to support “new music”, they were very keen. I think that the underground went above ground and good things happened. But by that time I had come to New York got involved in the No Wave scene here, so I never benefited from that change of political and cultural direction! I believe that to this day the MOC is helping people. MAGMA told me recently that they got quite a bit of help from them. Q: More particularly you stopped working with Magma after their double LIVE album I think it was? To me the original spirit of Vander and his music still lives on today, but it was not the same after that LIVE album musically or in terms of their overall evolution as a challenging, innovative group. What happened with the band? No, I produced UDU WUDU and MAGMA was still under contract to UTOPIA, my then partner got them to record ATTHAK. Frankly speaking, I lost interest after the cancellation of the UK tour and the break with Jannik. Unfortunately, most of the times, when a band hits the “top”, and there is real, substantial success, all kinds of conflicts appear. Most are rather childish and I just don’t have any time for that. Christian had a lot of plans, Stella, his (ex) wife wanted to own a studio and play a bigger part in the band, my partners were goofing it. OFFERING was started, solo records, etc. For me, the spell was broken. Q: Around 1978, some 10 years down the road from 1968, you came to the USA and staged the first progressive music festival in the USA – the legendary ZU Manifestival in NYC. Can you talk a bit about your reason for coming to the US and why you decided to promote a festival? I was involved with my UTOPIA RECORDS project, which had been financed by RCA and must have been one of the best independent label deals ever. I had some New York partners who unfortunately absconded with the money (what else is new!) and I had to come to NY to sort it out. It took a lot longer than I thought, so I had all this time and spent days walking around the place, I sort of fell in love with it. After the partnership resolution, RCA retained me as a “consultant” and I had a great time checking out what was happening. I came across a lot of underground NY scenes and musicians, and slowly the idea of linking the local scene with what we had been doing in Europe, began to wink at me. I got this house on West 24th Street and we began to put on experimental stuff. As you know some of the ”Eurock”(!) bands had become fairly popular with some college radio people and I thought it might be challenging to see if we could build an “alternative” circuit for “NU” music” here in the States, like we had done in Europe. The ZU MANIFESTIVAL was the result. I thought that if we could make enough noise in NY, it would carry us over to the rest of the country – or at least some parts of it. Man, I worked my guts out on that project. I put the whole thing together with $3,000 I got from CHARLY RECORDS in London for a NY GONG album idea. The first thing I had to do was to find musicians who would constitute the basis of a “house band” that could deal among other things with the European repertoire and GONG’s in particular since Daevid had agreed to come. This is where I found Bill Laswell, and it was the beginning of the ZU (house) BAND, later MATERIAL, but that’s yet another story. The NY event got absolutely great reviews and I was very encouraged. Little did I know what was expecting me on the next step!! Q: Who were some of the artists involved? Oh dear, mostly a combination of NY guys like Rhys Chatham, Glenn Branca, Theoretical Girls, and some 50 or so others, with Daevid, Chris Cutler, Fred Frith, Gilli Smyth, Yochk'o Seffer from MAGMA, etc., The show was sold out. It started on Sunday at noon and ended at 4am on Monday. At that time, the police insisted the theater cut off the juice and I remember Daevid, in a totally darkened theater, leading some 70 musicians and 1,400 spectators in a rave acoustic jam… Q: There was also another Manifestival a year later in Los Angeles. What was the idea behind this? Was it an attempt to form a bi-coastal music network in America, or? Well, as I said, the NY event was very encouraging, so for a follow-up some 4 months later I thought we take the show on the road and I started booking gigs across the country. I did learn a lot on college radio people – whom, with a few exceptions - I had never met. To me they all sounded very together and enthusiastic. Used to European underground conditions and collaboration ideas, I took most of them at their word, trusting their good faith, and confident they represented their local situations honestly so we knew what to expect. Well, some did and some didn’t and I found out how difficult it was to “do business” in this country. We ended up with about 33 gigs over a 3-month period, and if all went as it should we’d have established a “circuit”, or so I thought. Around the middle of March I put some 24 musicians in an old school bus I had acquired, and off we went. To this day I regret that we didn’t document that incredible adventure. I think there are a few photographs here and there, but nothing that could properly describe what befell us! There isn’t enough time to go into details now, but on the whole the 33 gigs turned out about one-third great, one-third middling and one-third disasters! Los Angeles belonged in the latter category. Early on when I was setting up the tour, I got a call from a fellow in LA who had some kind of a progressive label, can’t remember the name (Ed Note, it was Tony Harrington who had a label called ALL Ears Records). He was extremely keen to organize the LA venue and I was grateful to find someone who obviously had some experience – or so I was given to understand! Well, when we got there, I found there were all these bands on the bill he was producing/managing. Furthermore, the venue was a beautiful old theater, but on the wrong side of town. Very few people came and there was no money to pay us and he disappeared into the night! Having reasoned that LA should at least cover our expenses (about $1,000) we found ourselves stranded with no money whatsoever. Thank God, there was the school bus. My major concern (apart from feeding people) was to get the tour to the next stop, which was Phoenix, AZ, if I remember correctly. We didn’t even have gas money! So I spent 2 days and 2 nights tracking down this guy. A proper nightmare! I had never ever experienced anything like this. Some of us were watching his house, others his wife’s movements, others still his office. A real stake out. In the end we got about $100 out of him, enough to get to Phoenix. Alas, because of this guy, we got there late and the gig had been cancelled…Next… Well, after some more adventures, like running out of gas in the middle of the desert, the radiator blowing up, the transmission falling off and other such mishaps, we made it back to NY. By that time, everybody hated everybody… That was the first and last attempt on my part anyway, to try and set up an “alternative circuit”. I think that a couple of years later, the people who ran The Kitchen and other such subsidized venues, did put together a “package” called “New Music USA”, strangely resembling our earlier model, but without any European artists. Q: Which do you consider the most successful Festival in musical terms as well as environmentally? What I mean is did NYC or LA seem more tuned in to the progressive vibe you were trying to encourage? NY was a triumph compared to LA. The idea of “progressive” in LA had in fact nothing to do with what I thought the word defined. It appears to me it’s gotten even worse now. I went to the ProgFest in SF last year, the one with MAGMA and GONG, and, seriously. I found very little of interest musically. I think it all stems from the mistake of considering ELP and other such derivatives, as “progressive”. Most of the music seemed to be inarticulate noodling, sometimes approaching the kind of emptiness of New Age stuff or multi-layered noise replacing a true lack of compositional ideas. I read that the guitarist Buckethead is now playing with Guns ‘n’ Roses…The major problem seems to be the lack of good composers, IMHO, but also one of true artistic endeavor and quality. But this is a large subject and perhaps merits another forum! Q: With the dawning of 2001 we enter the new Millennium. How do you think the business of music today, and current social scene surrounding it has changed since the early 1960’s when you went to London and were involved in the jazz and R&B scene there? When I got to London in the mid-fifties, the “pop” scene was just a pale imitation of white US commercial music. At least there was a local “do-it-yourself” music, “skiffle”, (imported to the UK by British bandleader CHRIS BARBER) derived from Lonnie Johnson and other blues/folksters, which allowed young people to take up instruments. The Beatles started out as “The Quarrymen” and were able to inject some freshness into music when they started to make it. The Stones and the other blues bands introduced a new generation to black music thereby rendering an invaluable service too. European musicians were practicing jazz, and although aesthetically more appreciated than in the US, it seemed less urgent, less “dramatic”, less speaking to a new generation. So rock took over. Later the punks kicked everybody in the proverbial ---. This opportunity is still present, but bands/managers/labels are now so focused on making it in whatever category they and the “industry” define themselves to be, that a “major breakthrough” has become well nigh improbable. It’s the old story yet again, the seemingly tragic-comic vicious circle between the true function and merit of art and that of commerce and politics. Ultimately, it’s a question of education. I’m hopeful that the internet will allow the natural curiosity of those attracted to music to explore every nook and cranny of musical production and discover where the real values are and that bands will emerge who know what directions to pursue. Q: Magma still continues making music and some think that the whole experimental and progressive music scene is in revival. Do you think it can ever be what it once was in terms of creative spirit, or sales? 6 months ago MAGMA had their 30-year reunion, quite an event, I believe. So did GONG a year earlier, right? Jeezes, it seems incredible! I didn’t see these 30 years go by! But I also don’t see young bands coming up with that dedication to truly progressive music and the will to survive whatever difficulties to establish them. Perhaps in the jazz scene, there might be the possibility of new synthesis between “local” scenes, say Indian, Chinese or other ethnic music-sources and modern rock and jazz traditions. It could be a sort of World Beat improvisational affair but within serious writing “envelopes”, Harmolodic-Neo-Ethnic-Rock-Jazz-World Music!! I often ruminate about all this! Think globally and act locally is another element that I deem important. Music must resonate among the people, it must touch them because it describes them and their conditions, social, cultural and political, that allows for identification. In other words, it should be relevant to their lives. Q: Do you feel that people in general and artists in particular are still as open to new ideas and forms of music as they were before? Or has the new dominance of limitless technology and the culture it’s generated created a kind of short circuit between left-brain (technical / analytical) functions, and right brain (musical / creativity) processes? I think people in general are always open to ideas. They expect the artist to provide them, and that’s where the problem is. It’s a question of imagination and vision. Today it’s easier to use self-referential matrixes and templates. Machines are good at computing bits and pieces, sequencing, calculating. A hell of a lot of technology is truly amazing and timesaving - great for entertainment. But it still needs an overall design concept, a vision of the “bigger picture” so to speak, to create original art. From the printing press to the novel it took 200 or more years and it took the same amount of time to go from Mozart to Stockhausen. Things move faster now, but distances are still there, and the universe is expanding all the time as we speak. I like to think music will continue to be a measure of our experience on this planet. It’s a relatively small place (!), where before we move into the wider perspective of space, we’ll truly have to deal with additional dimensions! Q: You surely still have a passion for music and provocation/promotion, what are you working on today that we will hear about tomorrow? Kepler said that “the only constant in the universe is change” and change is scary sometimes. I like to believe that the purpose of art is that of making change less fearful so we can face it with more joy than pain, with more information and less confusion, and celebrate this mysterious state of “being alive” to its fullest. Learning from the past seems important to me, so right now I’ve embarked on collecting on videotape the “oral history” of rock in New York. I’ve been interviewing some 30 people, artists, managers, club owners, writers, DJ’s and just ordinary music lovers, who have witnessed key moments of the chronicle of rock in this city. I started a similar project in London and when I’m through with that, I’ll tackle jazz and the avant-garde. It will end up on an interactive website dedicated to oral history called ohblahblah, for …talk!). The Internet is perfect for this kind of thing. Q: If you could go back in time and do it all over again – the same way – or differently - would you? Good question! Going back has its advantages intellectually. You could correct errors you made, be forewarned, save a lot of time. Alas, it’s not possible. Doing it differently? I think at times that I should have insisted more on certain objective, practical aspects of life and perhaps less on subjective, aesthetic or moral issues, which made collective progress more difficult. Perhaps compromise a bit more? But I’m not sure even then; often compromise leads to a dilution of the original energy or vision. Who knows? Finally, we all have our tasks on this planet. Methinks, that all in all, I did the best I could. And I’m still here! - Archie Patterson

|

reviews features podcasts email bio

reviews features podcasts email bio