The Story so far...

1970's- FM radio, Alternative Magazine & 1st US Indie Distributor of Euro Rock

1980's- D.I.Y. LP + Cassette & CD label

1990's- Distribution via the WWW

2010- Eurock.com ~ Multimedia Podcasting, Interviews & Reviews.

Label & Artist Submissions Accepted for Review...

Klassik Krautrock

Artistes Français

|

|

UK Electronica

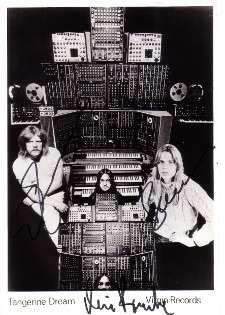

When Tangerine Dream signed to Virgin in 1974 and released Phaedra, their first album on an International label, the world of “Cosmic Music” expanded exponentially. The ripple effect of that continues to this day, as a whole sub genre now exists on the commercial fringes, composed of people inspired by the electronic sound pioneered by TD way back when. As a long time writer and promoter of that genre (which alternately at times feels like both a blessing and a curse) I’ve heard a lions share of what’s been produced by artists far and wide that contains elements of that original spirit. Upon consideration I’d have to say there are perhaps less than 10 Neo EM “groups” worldwide who truly nail the classic sound, and create something akin to the spirit of the golden age. In the UK, two musicians can be considered the pioneers of electronica - Adrian Wagner and David Voorhaus. Their original albums Distances Between and White Noise – An Electric Storm were groundbreaking classics of the genre. Mark Shreeve is one of the earliest UK synthesists to delve into the “Teutonic Electronic” realm, beginning with a series of cassettes he did in the early 1980’s for the UK Mirage and Norwegian Agitasjon fanzines. These led to his first LP Thoughts Of War, released in Norway on the indie label Uniton. The scene was much different back then, mostly word of mouth, and Eurock was one of the few outlets worldwide promoting/selling this sort of stuff. Throughout his career he’s done work for several labels, and had big selling titles, but never let his love for the glory days of analog electronics die as the albums of his latest group Red Shift demonstrate very well. Their three albums are rated by many as the best neo-Berlin School releases of the last decade. Another of the top current UK bands making some of the best neo-Euro EM today is Radio Massacre International. They seem to have channeled the spirit of the golden age into a slightly more modern hybrid of sound. If listener response were used as any measure, they would have to be ranked up near the top of the current Euro EM scene. They made a big splash on the scene in 1995 with the release of their debut double disc Frozen North on the Centaur label. Since then they have become perhaps the hottest selling indie electronic band from Europe. Their new album Planets in The Wires, released by the group themselves, may well have surpassed their debut in terms of musical creativity. This following interviews, done in the last month, shed some light on the who, what and why of Mark and Redshift, as well as the RMI trio. More on the UK Electronica scene will be forthcoming in future.

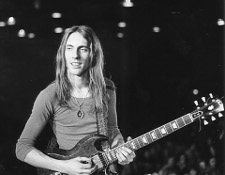

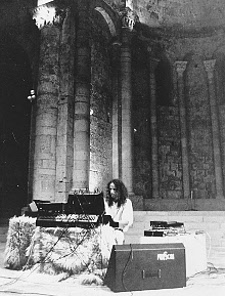

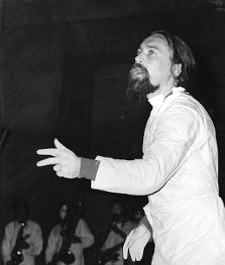

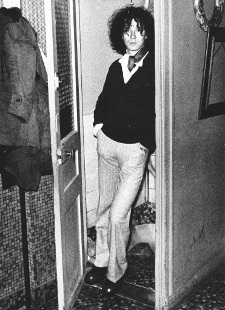

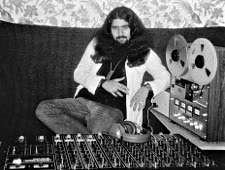

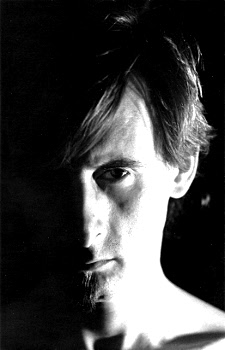

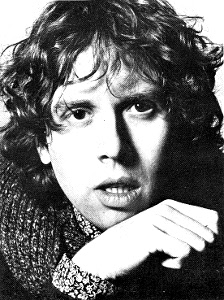

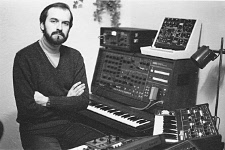

Mark Shreeve INTERVIEW

My first real experience of EM came when, as a child, I heard the theme music to “Dr. Who” (a cheap, but surreal show in the UK that started in the 60s). The sounds fascinated me (as well as the great theme). It was also the “atonal” qualities of some of the sounds that appealed to me too, the “other-worldliness” of their atmosphere. As I became a teenager in the 70’s I started listening to bands like ELP, Floyd, Zeppelin etc, the usual suspects. But I never quite got away from the weird stuff…obviously Pink Floyd at that time were a good supply of strangeness. A friends older sister played me Tonto’s Zero Time…this was a major discovery for me…an all-electronic composition. A year or two after that, I was laying back in bed (after a spectacularly unsuccessful girl-hunting trip at a local rock disco), listening to John Peel on BBC radio… hoping for some Floyd…. and he played “Mysterious Semblance..” from Phaedra. By chance, I had found heaven. To me, it was quite simply the most emotional and rather unsettling piece of music I had heard to date. From then on, I became hooked on German electronic music. Eventually, it became clear to me that I needed to express myself as a musician rather than just as a listener. When I could afford it (not for the first time, I was bailed out financially by my girlfriend), I bought a Yamaha synth…in 78 I think. I have been searching for the lost chord ever since. Did you ever really feel an affinity for the so-called sound and philosophy of “cosmic music”, or were you more oriented towards the more earthly plain (i/e scoring w/ the girls and making money, smile)? Hmmm…”cosmic music”…”girls”…”making money”… I’ve never been able to make that connection unfortunately. In fact, there seems to be no other form of music LESS likely to acquire those admirable goals than EM. I continue to do it because I feel a real “drive” to. I don’t know why exactly, but the urge to create this music remains as strong as ever. On the other hand, I don’t believe I have any deep philosophical agenda to pursue either. For me, music is about emotion, pure and simple. Most of the time I find creating music a very depressing experience, the only thing that keeps me doing it is, as I said, this strange self-destroying desire to hunt down that “perfect” piece… I know I shall never find it. What were the names of your early cassette only releases and what kind of equipment did you use back then? Did you tend to improvise like early TD, or work within more structured compositional structures? The first 2 cassettes released, simultaneously, by Martin Reed’s Mirage label were Ursa Major and Embryo. Followed quickly by Phantom…they were all put out in 1980 I think (although recorded a year before). The equipment for all 3 was basic… a Yamaha CS30 synth, Hohner K4 String Machine, phaser, flanger, all recorded onto a low speed Revox A77 which doubled up as tape delay machine. Improvising was all I could do at that stage…everything was new to me then, the technology, music, composition, even the playing (I had only ever played guitar originally). I would record a sequence line first, moving it, changing it constantly. Then I had to try and remember those changes while I added chords and/or top lines. The whole process was wonderfully organic, if a little primitive. When I listen to those pieces now they sound very raw, but they have heart…and the energy of youth. In retrospect I do think that Thoughts Of War stands up as a fine example of early, second generation EM. How did it come about that you got it released on a Norwegian label, as opposed to some UK outfit. Actually, Martin did release it as a cassette originally, but very soon after that Jarli Lastad, the mad Viking who ran Agitasjon in Norway contacted me saying there was a guy in Oslo who wanted to release T. O. W on vinyl and was prepared to pay for the pressings etc… so naturally I said yes. This was Tormod Opedal of Uniton Records. Do you have any idea how many copies it sold (I may be straining your old memory banks here)? I honestly have no idea…I would guess about 600 or so…based entirely on the number I’ve sold since of the CD re-release, but I may be wrong. The Uniton deal was for only that album, what happened after that one had come and gone? I think I lost track of you for a bit back then… Actually, Uniton released Assassin in ‘83 until Jive Electro signed me up in ‘84 and re-packaged it. My first “full” album for J/E was Legion, released in ‘85. Then in ‘87 I put out Crash Head, also on J/E. During this period I also got involved in writing songs for other artists, occasional soundtracks and some library music. In ‘95 I released Nocturne on the Sonic Images label…this was the last album I recorded as a solo artist (to date anyway). Since that time you’ve done a variety of releases for a couple different labels, major and indie. How would you compare the two types in terms of recording freedom, sales potential, business ethics and amount of money you have made for the various deals (that answer could well result in a doctoral thesis on the industry I realize, but maybe you can give it a go)? Hmmm. I think I’d rather talk about Jennifer Lopez… Jive was actually considered a “major independent” at that time in the 1980’s. I’ve always found that I could record whatever I wanted really. The only constraint being studio time and equipment hire costs. The experience (a first for me) of working with other people, engineers, producers etc was a huge learning thing experience. Not the least of which I had to come to terms with the fact that other people can have equally good musical ideas as me. It was a shock I can tell you. Musician’s egos are fragile at the best of times. Once I had got round this (after, I am ashamed to confess, some legendary tantrums) I really began to learn more about music…both technically and artistically. I loved that period…the proverbial “kid-in-a-sweetshop” scenario. I never felt any corporate pressure to change my music in any way. Obviously these kinds of record companies exist to make money…so by ‘89 when they decided that J/E wasn’t doing this it was folded. So basically, TD, Michel Huygen and myself were label-less. I never really felt bitter about it. They tried…and failed… simple as that…EM never became the big seller they hoped. I guess they never recouped the advances and studio costs that went into our albums… a common story. Legion alone amounted to about £65,000 in studio costs, and I believe the maximum sales figures worldwide were about 20,000. Now I’m no mathematical prodigy, but even I can work out that those figures don’t add up once you add promotion, advertising, packaging etc. Since then I have effectively “worked for myself”.... releasing albums as and when I feel like it. Clearly I can’t put anything like the funding behind it as a major can… but as I said before, If I was motivated by money, I would have chosen a different form of music altogether. My own experiences with record companies have generally been good… lucky for me I guess. Of all your previous releases, which ones still remain in print today? T. O. W., Embryo, Ether and Down Time…all are on CD. What is the situation in terms of the rights to all these old albums? All the old cassettes are mine, as is T. O. W. The rights to Assassin, Legion and Crash Head were bought up (at least the licenses were) by C + D Services. Nocturne is owned still by Sonic Images. Collide is mine as are all 3 Redshift albums. A couple years back you formed the group Redshift. The overall response to them has been quite good. Was the intent with that band to “go back to your analog roots”? Not specifically. I think one of the many reasons was as a reaction to the tedium I felt with all the “normal” E. M that had started to show up around the late ‘80s/early ‘90s. There were bands and artists (particularly in the UK and Europe) who were creating shockingly bland music…you know… cheesy little ditties over badly programmed drum machines using horrid thin digital preset sounds. People were releasing 5th rate soundtracks, to 4th rate films, that already had 3rd rate soundtracks written for them. In short… The Sci-Fi Anorak had hijacked European E. M. The “frontiers” style of E. M had been suffocated by all this “easy-listening-for-midi-nerds-elevator-music”. I was yearning to hear some darker, more unstable synthesizer music again, but no one seemed to be doing it. Around that time I purchased a few old analogue synths (some I had already owned years before) and started to really fly. It was as if I had totally forgotten how inspirational these instruments really were. I started to record some of these sessions (initially it was a solo thing). By chance I came into contact with Ed Buller who played me some earlier Node sessions on DAT. I was absolutely knocked out by what I heard…at last, someone was producing this huge, organic, threatening and above all, EMOTIONAL electronic music. Ed (and also Martin Newcomb of the Museum of Synthesizer Technology) managed to track down a Moog 3C modular for me. Now obviously, I had heard many recordings that had used this instrument over the years… but nothing prepares you for what it sounds like in the same room. It is quite simply a stunning sound… so rich, so powerful, and yet capable of so much delicacy too. I’ve been playing synths since the late 70s. I must have owned or hired dozens and dozens of different machines… and I’m telling you now… none of them even gets CLOSE to the beauty of a Moog Modular. It demands that you create music on it, there are no presets…keeping the same sound for any length of time is impossible… this for me is a virtue. All these computer plug-ins that are released now, you know…the ones that claim to be replicas of old synths… they make me laugh… they are truly terrible… these companies should be sued for making those claims… they aren’t even close to sounding like the real thing. I can only assume that it is hoped that the musicians who do use them have never heard a real analogue synth… or if they have, that they are tone deaf. I played a gig at KLEM ‘95 in Holland (under my own name to promote the Nocturne album)… and because I needed 2 other guys to help out we thought it would be interesting if we dropped in a more free-flowing sequencer based piece half way through. The crowd reaction told us all we needed to know... they went crazy for it. Moreover, it was more satisfying for us as musicians to play. When we got home the other 2 said, “why don’t we keep up with that style as a band?” (James and Julian by the way)… so effectively Redshift was born there and then. I had already finished most of the first Redshift album so the timing seemed right. You’ve done some live solo gigs over the years, as well as more recently shows with Redshift, how does the audience compare from one decade to the next in terms of size, gender types and occupation (OK, this is another higher education-type question, but for me these are very interesting things to ponder...)? I have a feeling it’s the same audience basically. Therein lies the problem with E. I feel that the easy listening mafia has really put off any new blood being attracted as listeners. When I first got into E. M in my early teens it sounded good to me because it was weird, dark, and yes…”cosmic” if you like. If I had been subjected to Turn of the Tides or whatever as an introduction to E. M. you would probably now be interviewing a Country and Western banjo player instead. The hardcore E. M audience are all getting older, some seem to have become rather jaded at a lot of the mindless pap being released and have left the scene (who can blame them?). Another strange anomaly is that the vast majority of E. M. fans are male. I have never really understood this. Good E. M. is surely amongst the most emotional music ever written. Maybe the lack of lyrics is the problem. It causes so much disappointment backstage after gigs too. You ultimately ended up starting your own label. Often musicians find it problematic to handle both the making of, and selling of their own music. What was your reason for this? Money. I had to be realistic about this. There was no way I could match the sales of Legion and Crash Head without a major company like Jive behind me. Some people did offer to release the Redshift albums, but the figures were ever so slightly in the rip-off area. It basically worked out that the label making the offer would rake in over 7 times the amount per CD than the artist would. It seemed totally unfair, and maybe another clue as to why E. M is slowly dying. It simply can’t afford those levels of individual greed. In terms of CD sales, how many copies did the Redshift releases sell? Not spectacular…the first Redshift has had a couple of re-presses, so it’s around 2,000 in total, say 50 of those as complimentary copies. Ether has done about 1,500, and Down Time about 1,200. (Well I did say we weren’t in it for the money!) How large of an actual audience do you think there is for this current “neo-electronic space music” sound? Well, call me Mr. Overoptimistic if you like, but…I have always believed that if this music got more airplay, sales would definitely increase. As a rule people don’t buy music they have never heard… so without airplay E. M relies on “word-of-mouth” alone. This doesn’t work. Tangerine Dream was regularly in the British album charts during the 70’s. They were also on radio a fair amount. During the 80’s, as their music became soulless and bland, the radio stations lost interest in them and their sales plummeted. Can you spot the connection? I live in hope that an enterprising D. J. will hear Redshift by chance… get totally chilled by us and start a new craze. You never know… after all, that’s how it happens for most forms of music. I’ve heard rumor now of a new Redshift release for ages. What’s happening with that? There is a live album ready to go and a studio album half way finished. All that is stopping us is… Yeah, you guessed…legal crap with an old publishing company. It’s taking forever to sort out, but it will get sorted… eventually. As one of the “old masters” of EM, do you now have a grand plan to explore the outer reaches of the cosmic, and conquer the pop charts in mind for that one (tongue firmly in cheek here), or perhaps some more humble plan for the future? A little less of the “old” please… In fact, just call me “master”. In many ways I feel as if I have all I want from life, I’m with my partner of choice, and I do exactly what I want when I want. The quest for extreme riches has abated considerably, that sort of thing doesn’t seem so important any more. Musically I feel drawn to creating these strange concoctions even though the process is quite painful. The end result usually is a desire to start the next piece and make it better… a never-ending circle with an unattainable goal. And like so many musicians, I keep at it even though I don’t understand why. As I recall, back when I was a teenager, I only wanted to be a musician in the hope that I would meet the blonde girl from Abba. There can be no finer reason for a life-quest such as this.

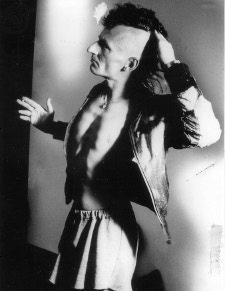

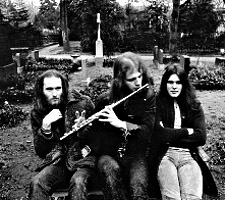

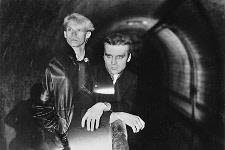

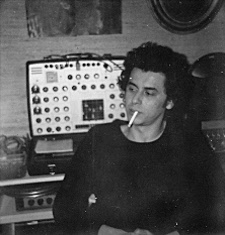

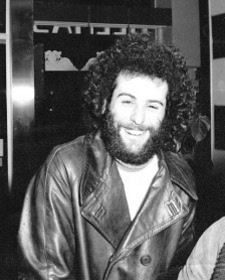

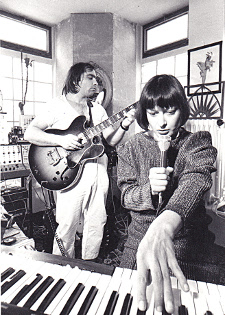

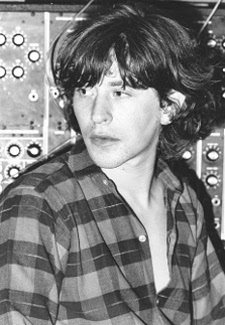

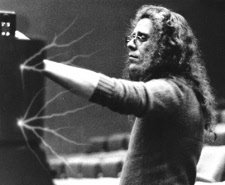

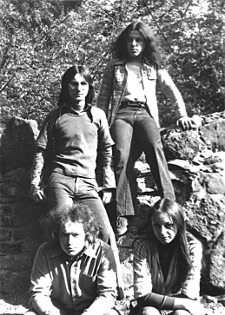

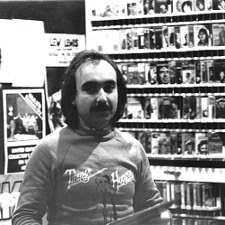

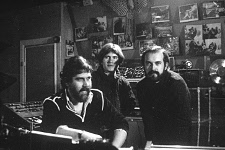

Radio Massacre International INTERVIEW

Let’s begin with some history. What was the intent behind the name, and how did you come up with it? SD: The name came about several years before the band in its current form. Duncan and I would occasionally sit around with an electronic device each rammed into the mic sockets of my cassette deck and would basically attempt to take signal overload to its logical conclusion, for the duration of a C-90! One day the name just came to me as a good enough description of these tapes. There is therefore no intent or literal meaning but rather three words that just sounded good together and arrived from god knows where. Who exactly comprises the band RMI, and where did you all come from musically in terms of previous musical experiences? The band is in Alphabetical Order: MR. STEVE DINSDALE – Keyboards, Drums MR. DUNCAN GODDARD – Keyboards, Bass MR. GARY HOUGHTON – Guitar, Synth SD: We have known each other since we were 16 years old; therefore many of our previous musical experiences were collective. Even before we started in 6th Form College (6th Grade), Duncan and I had already managed to get talking to a guy called Mark Spybey a second year student whose job it was at the recruitment day to extol the virtues of the History course. He saw the band names painted on my haversack (the usual suspects) and said that the college had a synthesizer (Roland SH 1000), which we proceeded to borrow for about three years! We started a band with him, and through Mark met Gary shortly after. Away from the band Duncan, Gary and I began to record in Duncan’s room, which rapidly became our first studio. We called the group DAS, and made a cassette album DAS 1/Earthdeath in 1980. We continued on this path and between 1980-7 DAS completed 12 albums none of which were ever released! (Mark Spybey eventually went on to join Sofornkontakt with the dearly departed Michael Karoli, and we had quite a reunion after 20 years at the Can Solo shows a couple of years ago!) There then followed the inevitable life changes, day jobs and so on. I played Drums in a couple of `scene’ bands after moving to London in 1988. Gary continued to play guitar, and Duncan continued to amass synthesizers at an alarming rate. He recorded lots of solo pieces during this time, and at this point we renamed the project Radio Massacre International. I eventually got disillusioned with the stupidity of the music business, as it became clear that the deeper you look into the abyss the less attractive and more like a job it becomes. Duncan and I had remained close friends in London throughout and it was inevitable that when he found a space big enough for us to work in that we’d get going again. `Startide’ was recorded at one of the first sessions in 1993. It’s an hour long and we couldn’t have cared less if it had been two! It was a great feeling of freedom, and with enough equipment to record everything straight to tape with no need for overdubs. Gary came back on board shortly after in early 1994, he arrived with his guitar and in that day we made `Drown’ (from Frozen North), `Diabolica’ and `Upstairs Downstairs’ (From Diabolica) in the time it would take my previous band to get a guitar sound they were happy with! Had you recorded anything previous to RMI? Outside of music what do you all do in the real world? SD: See above for answer to if we had recorded anything previous to RMI. Those DAS albums were quite different to what we do now, but there is a definite path that can be traced. We’re looking at ways of making this stuff available, but at an attractive price, as we believe it should be out there in some form. I also appeared on EP’s by The Honey Smugglers and TV Eye as drummer. In the real world I work as a Studio Manager for a Sports Media Group (TEAMtalk.com), Duncan is at MTV Europe as a Technical Manager, and Gary is in the big bad world of Corporate Finance. The main influence on your sound would seem obvious - Tangerine Dream. But when you first brainstormed forming RMI, was the central idea behind it to be `the new TD’ or something more? SD: To be honest we never sat and discussed our aims, even the very first time we recorded. It was always Duncan saying, “I’ve got some gear, let’s record”. We just do it and see what happens. The idea behind RMI was purely as a creative outlet, to make music that we felt was missing from our collections. It wasn’t even until a couple of years later that we actually found a deal and started putting it out. Obviously the TD thing comes up all the time, but in all honesty our influences are more universal than that. Electronic Music only makes up a very small percentage of our CD collections, and as far as our own music goes we simply see it as working with an established form the way you would if Jazz or Folk was your thing. As long as you come across with a strong personality of your own there’s no more to be said. I think RMI are readily identifiable and distinguishable from everyone else. DG: Not the main influence on the music, just the technology. The music we do has many influences besides other musicians. GH: We’re not the new anything! Our influences are from all sorts of areas as Dunc says not just musical. The only reason people continually refer to TD is because we use sequencers and Mellotron. It’s a bit ridiculous really; it’s like saying that all bands with bass Drums and Guitars are copying Elvis. When it comes to EM, personally I am an `old timer’ from way back in the days when new albums were listened to by candlelight, with incense burning, and visions of sacred spaces were conjured up. You are younger, and I wonder do you have any affinity for the concept of `cosmic music’, or does that seem outdated? SD: “Visions of sacred spaces” I like that! We tend to make large spaces with our music, and add detail, foreground, background etc. It’s a very good analogy. I’m not offended by the term `Cosmic Music’, although I would say not as close as to Brian Eno’s `On Land’ approach in that a majority of our more descriptive efforts tend to refer to earthbound spaces like the Frozen North or Gulf. Albums like Startide and the album we made live at Jodrell Bank Radio telescope could obviously be described as 'cosmic’ which is fine, but it’s not all we do. I would define Cosmic Music as `that which describes the wonder of space’, and yes we certainly have. GH: What you’re describing is not unlike the experiences I used to have when I first started listening to some of the more spacey music. To be honest we just turn on plug in and play. What you hear on the CDs is the end result. Some of it is pretty cosmic though – like Zabriskie Point or ‘Blakey Ridge’ (from Borrowed Atoms). Everything today seems much more equipment oriented and digitized. What equipment do you guys use, and do you prefer the old analogue sound, or? DG: Whatever we feel like using. People will point at the mellotron and say, “why don’t you use samples instead?” they don’t sound the same, but that doesn’t exclude them from the armory. Recent material has used the mellotron less, but the analogue synths more. A few years ago, we weren’t using analogue synth sounds at all for sequencing. As far as the recording process goes, we’ve always used a mixture of analogue and digital techniques and equipment. The basic philosophy with instruments and recording gear is to use whatever best meets the needs of the circumstances. We have the luxury of having a choice. Instruments or other studio gear that don’t pull their weight or do their job to a satisfactory standard are quickly discarded. We really just tend to mix and match and certainly don’t stick to any one set up. We tend to prefer a small mobile and intelligent approach rather than looking like a synth museum. We use the Doepfer MAQ16 to drive two Moog Prodigy’s for sequences on the fly, and we also have the superb Lactonic Notron which is a little less immediate to use but can provide some superb sequencer functions like triplets and allows for a huge frequency range. One person could physically carry both units under each arm and that’s the way we like it. GH: Strat, Marshall, Fender Twin, MXR Distortion, Jam Man, Line 6 Delay, Cry Baby Wah Wah, and sometimes a bit of flange can be nice ….oooooh matron! * (*English Humor SD) Much of your material is recorded live, is there a reason for this? SD: Not sure if you mean live `In Concert’ or live in the studio, but either way there is an immediacy that is captured when music is happening live in the here and now. Musicians behave differently when they are on the spot and improvising rather than playing through a rehearsed piece. This is exaggerated when there is an audience there too. We have become used to recording straight to two-track tape/DAT, and hence the mixing process happens as part of the improvising process. It may not always be perfect, but it eliminates the possibility of tinkering with the mix endlessly after the event! There’s far too much time wasted in studios generally, (Again from previous personal experience!) and I would always point to the fact that `Kind Of Blue’ and `Astral Weeks’ were each recorded in two 4-hour sessions! They are both in many people’s all-time Top Tens and still sound incredible technically. Making records is a lot easier than many people would have us believe, just get in there and do it! DG Yes- it’s quicker and easier. We have a limited amount of time to capture this stuff, both because of our circumstances and because we’re adept enough at improvisation to have escaped forever from the repetitious rigors of arrange/rehearse/record that, in other bands, detract from the creative flow. Do you compose pieces in advance, or perhaps follow the more improvised tradition? DG: Both. After a while, we realized that live performances would be more satisfying if a) we had a “warm-up” period working through something we all knew the basic framework of, but that still allowed some improvisation and b) the audience would appreciate hearing live versions of familiar material. Not, surprisingly, such a great technical or musical challenge to reproduce improvised pieces on stage, but sometimes it takes a while to dismantle an older piece into its components for a live recital. Most studio work is purely improvised, safe in the knowledge that we can edit out howling mistakes or bits that didn’t work. The editing then becomes an element in the shaping of the finished piece. Live, we have tried every approach from 100% improv. to 50/50. Pure improv. tends to work best within a set also containing pre-written frameworks. Quite often it isn’t particularly useful to hear one complete improvisation after another and this approach is rarely successful. If we are doing one concert a year then that hour on stage has to be good, and not an aimless wander in an electronic wasteland of our own making. GH: Even our composed stuff is very loose. Generally we will have an idea for the feel of a piece and the key. That’s all we really need. How many live concerts have you done, and what kind of attendances do you achieve? SD: We tend to manage at least one concert a year, although we’ve clocked up about twelve to fifteen in about six years. The largest audience was 1,000 in Nijmegen at the Klemdag, and we played in Huizen at the Alfa Centauri Festival 2000 in front of about 300. Jodrell Bank planetarium is much more intimate (150), but we have played some good music there over the years, having done concerts there in 1996,1997 and 2000. We had a series of pub/club gigs in London between about 1995-7 too, which were largely `Never Again’ experiences, but sort of fun in a masochistic way. It meant that we were sharing the bill with indie bands and were at least something of a curiosity. Of course our largest audience would have been our MTV Europe live appearance in 1996, technically speaking! How large of an audience do you think there is for this neo-electronic space music’ sound? DG: Even if no one bought the stuff we’d still be doing it! We couldn’t really care less how large the audience is, but there’s no denying that it isn’t exactly expanding exponentially! The potential audience is a lot bigger, but people are just simply not aware that we’re out there. They’re too busy being spoon-fed by the Marketing Depts. of the major labels. We would be kidding ourselves if we pretended we were ever going to be suitable for mass consumption though. In terms of CD sales do you have any idea what was the most popular of the albums put out by the Centaur label? How many copies did it sell? SD: Our two top sellers have been Frozen North and Borrowed Atoms, the latter of which has been the most critically acclaimed. I guess we’re talking about maybe 1,200-1,500 sales of Frozen North which doesn’t seem much, but then imagining them all in a room together it does… especially if they each offered to buy us a drink! Frozen North might be enough RMI for some people, after all in old terms its 140-minute playing time is equivalent to 7 old sides of vinyl! Similarly Borrowed Atoms is also a double CD, and the one, which perhaps comes closest to refining the `classic’ analogue sound. We aim to make each release as good as the last and more importantly, to have an identity of its own. There’s no telling what people will like, in fact signs are that Zabriskie Point is proving to be very popular, which pleases us as it’s truly on its own musically without even a sequencer in sight. Your sound has seemed to change a bit on recent releases, do you listen to much music outside the band and perhaps this has broadened your sonic palate? SD: The music has evolved and changed completely naturally, we tend to view the making of music and the consumption of it separately, so there’s no way one could influence the other. We just look for new approaches and new gear configurations, plus as improvisers we are always subject to the circumstances in the studio on that particular day. It’s only when we look back that we realize that the sound has changed over time, and it’s hard to pinpoint. You also just started your own label. Often musicians find it problematic to handle both the making of and selling of their own music. What was the reason for this? SD: Complete control over everything! We felt that maybe we were an established enough name to take a small risk and make our own product. We feel that we have made the most effort to promote and publicize the band ourselves, so we should reap the rewards. We have controlled all other aspects of production from day one. The only likely problem again might be the fact that we don’t have a huge database of customers, however the internet has been an enormous help in allowing bands to sell their own music and long may it thrive. We also have a good relationship with a few outlets that can guarantee a certain level of sales, and have had invaluable help in those parts of the manufacturing process we are as yet unfamiliar with. It seems there is a ceiling on the genre that limits the level of success that a group can achieve. The only way to break through is with a product placement in a film or major media event. Do you have a future marketing ‘master plan’ or will you let the cosmos decide? SD: We’ll leave it in the lap of the gods! As Gary says “It’s not like we’ve just turned down Sony or something!” The people that buy our music are discerning and they have to actively seek out the CDs and discover the music for themselves…they buy the music they want to hear rather than being sold it. Many artists who I regard as being geniuses never broke through to the mainstream and they’re not meant to. Most music is consumed on a very superficial level, which sounds snobbish but it happens to be true. We’ve been on Radio 1 (Major BBC national Music Station), the BBC World Service, BBC2 TV (Music featured in a documentary about Jodrell Bank) and MTV Europe and it has made very little difference to our sales. To really sell records you need a £300,000 promotional campaign, where you are shoved down people’s throats on a continual and uncomfortable basis, or like you say to be prominently featured in a big movie. The whole thing is such a multimedia mass marketing exercise designed to maximize sales for conglomerates that probably own the film and the music on the soundtrack. Our music could work well as film soundtrack, but these days it’s all about squeezing in all these has-been bands whose publishers are trying to rehabilitate their careers (he said, cynically) The great thing about the seventies was that there was a genuine underground feeling and mystery to discovering your own band. We’d like to feel that a little of that spirit survives in what we do. Of course we’d like to sell lots, but we understand why that’s not going to happen! It’s important not to be financially reliant on the income we make from the music and therefore artistic freedom is maintained. We’ll just keep on doing what we do! - Archie Patterson

|

reviews features podcasts email bio

reviews features podcasts email bio